Brain in a Box: The Science Fiction Collection. Rhino Records, 79936, July, 2000.

By Kay Dickinson

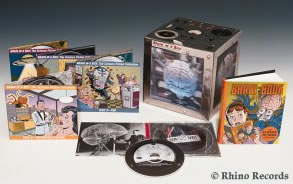

The Brain in a Box draws together, in one lushly hologrammed trophy container, a wealth of musical variations on the theme of space and science fiction. Lift the studded metal lid and you’ll find five CDs (Movie Themes, TV Themes, Pop, Incidental/Lounge, and Novelty) and the hardback Brain in a Book which trawl through sci-fi from its high-minded inventiveness to its cheapo schlockishness. Spoiling us with a plethora of poster and still reproductions  at every available opportunity, the book roves through the history of music and sci-fi unions (such as Offenbach’s Le Voyage dans la lune), including film plots that draw on music for their narrative themes; it even throws in a bit of meaningless banter from Ray Bradbury for good measure.

at every available opportunity, the book roves through the history of music and sci-fi unions (such as Offenbach’s Le Voyage dans la lune), including film plots that draw on music for their narrative themes; it even throws in a bit of meaningless banter from Ray Bradbury for good measure.

Within this same book, the compilers state:

our quest for the best, the coolest, the must-have tracks, we, the producers, went to aficionados all over the country and sifted through hundreds of just about every intergalactic recording you could possibly imagine. (4–5)

This highlights the toil that’s gone into the package, the extent to which the team has admirably fulfilled two key subcultural criteria: painstakingly researched esoterica and a fetish-friendly collectable with all the trimmings of a smart investment for the future. However, just as Brain in a Box grants its owner the finest mantelpiece in all of sci-fi-dom, it also comes up trumps as an archive of intriguing and often genuinely innovative music that may not have survived very long had it not been for obsessive hoarders within the sci-fi community.

However, while the scope of Brain in a Box is impressively wide, there are nevertheless a few glaring absences. On the whole, the chosen tracks come from English-speaking nations, mainly the US. Also, none of the themes from Star Wars are to be found, an unsurprising result of their licensing costs. Yet what self-respecting sci-fi muso would have dared to leave out—as Brain in a Box has—Wendy Carlos, David Bowie, or, in fact (Jefferson Airplane aside) all the late sixties references of the Dark Side of the Moon? Parliament’s “Unfunky UFO” is the box’s single concession to funk, a genre which puts much store in the extra-terrestrial, and Sun Ra’s complex philosophical/political investment in the celestial only sneaks in a brief appearance with “Space is the Place.” What’s more insulting is that the Parliament track is wedged onto the Novelty CD (while They Might Be Giants resides in the higher status Pop one) and Sun Ra sticks out like a crash-landed sputnik amidst two tupperware party mood-makers on the Incidental/Lounge volume.

In some ways, this clashing track order exemplifies everything the box set stands for—musical diversity. At times, however, the constant jolt of being thrown from genre to genre gets a little wearing. The eeriness of The Twilight Zone’s theme is trampled over by the boisterous adventure tales of Lost in Space and My Favorite Martian. These are then followed by the intangible Dr. Who credit music which we have little time to settle into before an about turn into the brash‘n’bouncy cartoonish introduction to The Jetsons. Likewise, the muted understatement of the first song from The Rocky Horror Picture Show loses all it has subtly built up when succeeded by the comparatively heavy-handed bombast of Also Sprach Zarathustra.

While this ordering is unfortunate and does some of the music an injustice, it evidently springs from an eagerness to showcase the sheer range of musicians who have made reference to the extra-terrestrial. Unlikely sources include Ella Fitzgerald and offerings from such genres as rockabilly (Bill Riley and his Little Green Men), bluegrass (The Buchanan Brothers and Georgia Catamounts), big band (Chris Conner and many a TV theme), garage (The Marketts), surf (The Rubinoos), hippy rock (Jefferson Airplane), pop folk (Prelude), country (Mojo Nixon and World Famous Blue Jays), new wave/alt rock (B-52s and Suburban Lawns), and the small tightly packed bullets which traditionally constitute music for animation.

Much of this music fails to divert from its generic course to accommodate the theme at hand. Sometimes, especially when songs are sci-fi in lyric alone, it is as if space were a quick and obvious cash-in rather than a core inspiration to the composition. To add to this, many of the pop songs included in the set are particularly gimmicky. Novelty tracks like Louis Prima’s “Beep! Beep!” and Buchanan and Goodman’s “The Flying Saucer (Parts 1 and 2)” have narrative twists, so they only work properly once. Irritating as these numbers can be, they do betray the effect aliens have upon the popular consciousness, including the desire to jest in the face of anxiety—something immediately recognizable to fans of almost any musical genre.

Moreover, if these tracks make us feel that a trend is being cynically jumped upon, then they are only mirroring the way much sci-fi traditionally works. Along with horror, sci-fi has stood proudest as the genre most likely to be cost effective, exploitative, and malleable to contemporary (often teen) tastes, traits which need not necessarily work to an aesthetic disadvantage. Leonard Nimoy’s “Music to Watch Space Girls By” glares forth as exploitation at its purest and most unabashedly parasitic. It uses a musical standard as its safe foundation and slap-dashly plasters it with some airy organ sounds and vocal choruses to imply the added word of “space.” As this track and many others in Brain in a Box point out, the exploitation angle is not solely drawn upon to appease the adolescent audience. Lounge-y Les Baxter also leaps on the bandwagon with “Saturday Night on Saturn” (which is extra-terrestrial in bank-rollable name only) and “Lunar Rhapsody” (which deviates only from his house style courtesy of an inorganically tacked-on theramin section).

Of course, what space had to offer the suburban cocktail set was not the thrill of the lurid B-movie, but the opportunity to show off one’s brand new luxury home stereo. Postwar domestic decadents evidently delighted in what the vastness of space could be translated into musically, from its sophisticated wide-ranging orchestration to, more importantly, the up-to-the-minute panning and swooping of which such pieces as Russ Garcia and His Orchestra’s “Nova (Exploding Star)” take advantage. The cutesy twinkles of electronica in Perry Kingsley’s “Cosmic Ballad,” although of the same genre, betray a much more experimental bent to the space theme, one which afforded a host of composers the chance to push their ideas to the outer limits.

In many ways, space and all its unknown dimensions licensed a form of orientalism in its best and worst forms. For example, Russ Garcia’s “Frozen Neptune” patterns the “other” of outer space on oboe and flute motifs which are stock phrases and timbres that Hollywood composers and lounge bands alike often used to evoke the “non-Western.” Yet, just as sci-fi in the form of, say, Dr. Who and The Thunderbirds has imaginatively exceeded the limitations of tiny budgets, the genre has done the same for composers who, far from fearing the encroachments of science, have embraced them in specifically musical ways. The warped pulsing and pattering of the Forbidden Planet soundtrack is a non-“melodic” landmark in popularly received music, being one of the first scores to rely primarily on electronically generated sound. According to the Brain in a Book, Forbidden Planet’s score “was billed not as music but as ‘electronic tonalities’ reportedly because the musicians’ union, back in 1956, would not accept electronic sounds as music” (17). Similarly, the texturally visceral tickings of the Fantastic Voyage soundtrack mingle with “other worldly” laser sounds; Frank Coe’s “Tone Tales From Tomorrow” stretches at the semantic boundaries of “music;” and the Andromeda Strain score uses the excuse of a paranoid film narrative to build a nervy serial piece up to a climax of electronic fuzzes, bleeps, and blurs.

What arises time and time again on these tracks is that the labeling of electronically produced sound as inorganic was—and still is—the strongest signifier of “technology.” Although electronic intervention is unavoidable in reproduced music at least in terms of amplification and recording procedure, conventions of understanding still assume electricity to be futuristic. Thus even films without avant-garde pretensions (such as The Creature from the Black Lagoon and The Incredible Shrinking Man) meld electronics with an orchestral sound in their scores. While some spheres of music-making have shunned the obtrusive use of electronic hardware, the potential for sci-fi to symbolize “the unknown” through unfamiliar instrumentation has consistently offered these types of equipment a forum.

Of these, none is more prized than the theramin, a device invented in the early 1920s and virtually unused outside its role of “space-signifier.” The ethereal glissandi and smoothly textured timbre of this instrument, one of the few where one touches air rather than keys or strings, seems ideal for bringing to mind the cold expanses of outer space and the swooping space ships which travel across it (something which is similarly conveyed by the breezy electric organs on The Tornadoes’ “Telstar” and steel guitars and tremolos on The Ventures’ “Fear”). In scores like The Day the Earth Stood Still (which combine theramin with harp and orchestra) and One Step Beyond (where it closely matches a female choir singing “aahs”), the theramin’s proximity to the human voice becomes apparent. Similarly, the more recent X-Files theme spotlights a whistling sound which seems just about mechanic, but distinctly humanoid. Here such instrumentation excels where elsewhere it might seem to infringe upon clearly human capacities. The theramin and its relatives confuse us about their origin at exactly the point where sci-fi loves to linger—the very question of what constitutes “the human.” By sounding at once organic and inorganic, the theramin is a very precise musical indicator of everything the cyborg has asked sci-fi fans to interrogate about human boundary lines from Frankenstein onwards.

Nowadays, the theramin resides mainly in its temple of pastiche, appearing in deliberately retro endeavors such as Mars Attacks and The Simpsons (both featured on Brain in a Box). Yet, while the theramin has had some of its luster dulled by constant use, its continued recurrence betrays a strong and easily comprehensible linguistic tradition in sci-fi music, something which other aspects of this box set also make abundantly clear.

One of sci-fi film’s key features—a devotion to the spectacular—is consistently paralleled in the sonic register. Just like the image’s awe-inspiring stunts, these soundtracks encourage us to be enthralled by technology almost for its own sake, sometimes even at the expense of narrative involvement. There are distracting exaggerations, quick mood changes, dynamic extremities and, above all, an expanded sense of musical space. Octave leaps carry this idea through compositionally, while production techniques make the tracks seem cavernously vast or overtly directional—like Bill Carlisle’s “Tiny Space Man” where space ships seem almost to be whizzing past overhead. Again, the links to sci-fi cinema are strong. This is not far from the preoccupation that led George Lucas to insist that his movies only play at cinemas with the most up-to-date multi-channel sound systems so that audiences might mistakenly duck X-Wing fighters or feel the thud of AT-AT walkers through their seats.

But the musical language of sci-fi isn’t totally focused on technological teleology and “the new.” Musics conventionally circumscribed as “divine” through their slightness and ethereality have been hijacked to imply “things from above” in ways that most people would readily understand. The most frequently stolen idiom seems, unsurprisingly, to be nineteenth–century symphonic composition—something that already bore a popular currency for evoking the majesty that outer space seems to require and that slotted in neatly with the scoring heritage of the classical Hollywood period. Soundtrack after soundtrack (The Time Machine, Them, The Thing, Alien, The Fly, E.T. and so on) returns to this style to create the strident questing themes so central to many a sci-fi narrative.

Yet, as Brain in a Box also reveals, there is scope to warp these orchestral sounds under the clause that space is “unknown.” Jerry Goldsmith’s work for The Planet of the Apes is interrupted with a much less standard sense of tonality than your average Hollywood soundtrack. The Outer Limits employs sharp string sounds which imbue even this most mainstream of entities with a touch of discordance and The Matrix manages to balance European modernism with more palatable Romantic ideas. In each of these instances, the sci-fi genre and its obsession with paranoia, anti-realism, and difference allow free rein to the kinds of musics that are so often suppressed for the standard popular audience.

While musical science fiction bounces from exploitation to experimentation, symphonic opulence to electronic sparseness, and from pop familiarity to unnerving atonality, it can only hint through opposition at perhaps the most pervasive sound of outer space—silence. Sure, we are exposed to moments without sound in many of these scores and pop tunes, but silence does not a good TV theme make. In the event of absence (of sound and of knowledge about what lies beyond), we create a vast range of musical objects to fill the gap. Here we reach the nub of sci-fi, that all these interpretations of space say more about us—our fads and phobias, preoccupations and politics—than they do about “them.” As mere earthlings, we have specific desires that need to be met. When it comes down to it, sci-fi audiences demand value—or rather values—for money, and you can’t really sell a box set full of sonic nothingness.

Kay Dickinson

Middlesex University