Building Culture: Reflections on September 11 from Amman, Jordan

Anne Elise Thomas, Brown University

On Tuesday, September 11, at 4:30 pm, I was at the National Music Conservatory in Amman, Jordan, preparing to videotape a workshop by a group of musicians visiting from Lebanon. I had been in Amman just over a week, beginning my dissertation research on youth involvement in Arab music, and was still very much learning my way around. [Author pictured right]  The workshop I was preparing to document was part of a large-scale event called “Souk Ukaz,” a “Marketplace of Culture,” designed to bring together artists, performers, and cultural producers from various nations to display their work and to exchange strategies for cultural production in a global marketplace. In recent years, Amman has been trying to become a center for culture and business in the Middle East, and through events such as Souk Ukaz, organizers hoped to showcase Amman to a wider audience.

The workshop I was preparing to document was part of a large-scale event called “Souk Ukaz,” a “Marketplace of Culture,” designed to bring together artists, performers, and cultural producers from various nations to display their work and to exchange strategies for cultural production in a global marketplace. In recent years, Amman has been trying to become a center for culture and business in the Middle East, and through events such as Souk Ukaz, organizers hoped to showcase Amman to a wider audience.

As the workshop was about to begin, Kifah Fakhouri, director of the conservatory, told me that something terrible was happening in the United States. Several planes had crashed into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. We tried to check news websites for more information, but there was too much internet traffic to access these sites. At that moment the group showed up and I left the office to videotape their workshop. After the workshop concluded, the reality of what had happened was beginning to sink in. “I hope this was not done by Arabs,” people were saying, already considering the repercussions if the terrorists were discovered to have Middle Eastern citizenship. I went home, tuned in to CNN, learned what had happened, and cried with the knowledge of the thousands of lives that had been lost in a few short hours.

People in Amman, as in other parts of the world, were shocked at what had happened. Many were concerned about relatives and friends living in the United States, and they mourned several Jordanians who lost their lives in the attacks. When I introduced myself as an American, people offered their condolences and their hopes that my family and friends were not affected by this tragedy. As part of my research, I had been keeping a log of the music I heard in taxis, stores, and other contexts; for days after September 11th there was no music in these places. All radios were tuned to the news or turned off. A candlelight vigil was held at the Amman citadel in remembrance of the victims, and flowers were left at the American embassy in an expression of sympathy.

In the following weeks, my research was my therapy. I spent my time observing young people learning Arab and Western music at the conservatory. [Pictured right] Activities there were not seriously interrupted by the attacks, although some of the events planned for the fall were canceled as visiting musicians and groups decided not to travel to the region. One of the teachers at the conservatory had been planning to take his Arab music group to the United States for a three-week tour starting September 12; needless to say, their trip was canceled. After spending countless hours rehearsing and preparing for this tour, the group suffered both a loss of income as well as a psychological setback.

although some of the events planned for the fall were canceled as visiting musicians and groups decided not to travel to the region. One of the teachers at the conservatory had been planning to take his Arab music group to the United States for a three-week tour starting September 12; needless to say, their trip was canceled. After spending countless hours rehearsing and preparing for this tour, the group suffered both a loss of income as well as a psychological setback.

While life in the United States was changed dramatically following the attacks, in Jordan the most disruptive effects of the tragedy were yet to be felt. Jordan’s economy, already suffering considerably from the year-old Intifada in neighboring Palestine and Israel, has slumped since September into even more serious recession. The number of travelers coming to Jordan has dwindled to virtually nothing. The tourist industry, which in recent years has invested a great deal in developing infrastructure to attract foreign visitors, found its much hoped-for “peace dividend” pushed even farther out of reach.

Musical life in Amman has suffered the effects of Jordan’s economic slowdown. Concert attendance is down, and while it has never been easy for musicians to make a living through performance in Amman, now it is next to impossible. The National Music Conservatory has been dealt a serious economic blow as well. The NMC is a relatively young institution, founded in 1986 as a string program for young children. In 1988 they expanded their curriculum to include a wind program and an Arab music program. Initially supported by funds from the Noor al-Hussein Society, the conservatory has been struggling to achieve self-sufficiency since the death of King Hussein in 1999. The NMC now relies on significant support from private donors and institutional partnerships as well as student tuition.

Currently, enrollment at the conservatory has dropped to around 50% of its normal capacity. A majority of the students enrolled at the NMC are from Palestinian families, reflecting the social structure of Amman as a whole, and since the Intifada began last year, many of these families have been reallocating funds to support the Palestinian cause. Private donations to the NMC have dried up as well, “because all of the money was going across the river,” says Julie Carter Sarayrah, Associate Director of Development at the NMC.

At present, the Palestinian/Israeli conflict continues to escalate, and with the US strikes in Afghanistan and talk of possible U. military action against Iraq, the situation in the Middle East is looking increasingly unstable. Jordan, itself allied with the United States, remains relatively calm, although its location between Iraq, Syria, Israel, and the Palestinian Territories means that Jordan experiences direct effects of regional instability. A large number of refugees from Iraq and other Gulf states came to Jordan during and after the Gulf War, and since the latest Intifada began, more Palestinian refugees have arrived.

The conservatory’s history has been shaped by Jordan’s role in the region as well. The staff of the NMC has always included many foreigners, including people from Arab nations as well as from Russia, former Soviet states, Europe, and North America. With the Gulf War in 1991, many of these faculty members left Jordan, and the NMC found itself with a serious teacher shortage. At the same time, the NMC had developed relationships with a number of musicians from Baghdad who had been trained in Baghdad’s prestigious Fine Arts Academy and High School for the Performing Arts. Several of these musicians also studied in Russian conservatories, and all were highly accomplished performers in Iraq’s national symphony orchestra. As opportunities for musicians in Iraq were severely limited after the war, the NMC invited these musicians to come to Jordan and join the conservatory staff. These musicians formed the backbone for the National Music Conservatory Orchestra, established at around the same time, and they continue to form an essential core of the teaching and orchestra personnel at the NMC.

One of these musicians is Mohammed Ali Abbas, now a violin and viola teacher at the NMC. I take weekly lessons with Ustaz Abbas on Arab violin, and I recently discussed these issues with him. To him, music and culture have an uneasy relationship with politics. Musicians, he suggests, make it their goal to build culture and to develop their own potential, thus enriching society and contributing to humanity as a whole. This is why, he says, in spite of the effects of the Gulf War, subsequent embargoes, and other hardships, musicians in Iraq are still actively performing, composing, and teaching music. “Serious musicians,” he says, “they like to build themselves, because they know the situation…doesn’t go back again, it takes time. So they must use this time for themselves, to grow, in music. Because otherwise it will be lost time.”

Politics, says Ustaz Abbas, contributes little toward cultural development, and he is suspicious of politicians who claim to support the arts, but who in reality make these gestures for political gain only. He observes that in the Arab world, a country’s wealth seems to have an inverse relationship with the status of music in those countries. The wealthiest nations in the Arab world, he notes, tend not to promote musical activity. He blames this on a feeling of complacency on the part of these nations; a feeling that having money is enough and there is no need to develop their human potential further. When you visit these countries, he says, you see nice buildings, but no richness of cultural life. And as we have all been made painfully aware, buildings are destructible. Culture, on the other hand, is the hardest thing to develop, but it is the most valuable and lasting monument a civilization can achieve.

The optimism that colored my first week in Jordan, as I experienced Souk Ukaz and Amman’s vision of itself as an up-and-coming cultural center, suddenly changed hues as the events of September 11th left the world in shock and mourning. This tragedy was put in a different context, however, with the realization that people here in the Middle East have been living for decades with violence and the painful disruption to daily life that it brings. As an American, I have been granted the luxury of peace and political stability, and the added luxury of taking these things for granted—luxuries that have made my career in music that much easier.

UNESCO has designated Amman to be the “Cultural Capital of the Arab World” for the year 2002, and preparations are busily underway for this event. Government ministries, arts organizations, and the royal family have been visibly organizing and promoting activities for the yearlong project. The NMC will be heavily involved in planning the musical components of this event, which will include festivals, concerts, and the release of a seven-CD anthology of Jordanian music. Musicians and administrators at the NMC are hopeful that these projects will bring much-needed recognition of the importance of music to Jordan’s cultural life. In spite of the hardships they face—political, economic, and psychological—musicians in Amman are continuing to build their culture.

| My research in Amman is made possible by a fellowship from the Council of American Overseas Research Centers and the American Center of Oriental Research. I would like to thank the following for their contributions and assistance in preparing this response: Julie Carter Sarayrah, Mohammed Ali Abbas, Kifah Fakhouri, Zina Koro, Susan Gelb, and the National Music Conservatory. |

Introduction by Timothy Rice

I’d like to welcome you here this afternoon to participate in our roundtable on “Music, Community, Politics, and Violence: a Musical Perspective on the events of September eleventh and since.” Before we begin, I would like to thank the Ethnomusicology grad student organization for helping to organize and produce this event.

If you’re not from the Ethnomusicology Department, then you may be surprised that there are musical perspectives on the events of September eleventh. If you are surprised, I think it probably comes from the fact that in our popular culture music is construed, first of all, as a kind of entertainment, and therefore a distraction from the kind of serious events of everyday life. If it’s not an entertainment, then may be an art. And while that art requires a great deal of dedication—and even genius—to pursue, it’s often believed that the art exists completely cut off from everyday life, and that that’s one of it’s great joys.

Ethnomusicologists would agree that music is an art and an entertainment, but we also know that music is much more than that. Music can be a therapy and can heal; it can be a commodity with great commercial and economic value; it can be the ground on which cultural and ideological issues are contested; it can be the place where people learn to form and enact important aspects of their social identity. And so for these kinds of reasons a musical perspective, I think, can be relevant to our understanding of these events of September eleventh.

The fact that current events continue to demand some form of education is brought home to us daily, I believe, in the news media. We still see national network broadcasters feeling somewhat comfortable displaying their ignorance of this part of the world by joking about the “stans,” as if these countries and their cultures and their languages and their musics were perhaps too difficult to distinguish, and can therefore can be dismissed as the “stans.” And I just heard on the radio this morning a radio broadcast that in Orange County in the past month since these events, there have been twenty-six hate crimes committed against people who looked middle eastern: more hate crimes in one month in Orange County than in the entire previous year. So it’s clear that we all—we on the stage and you in the audience—have an ongoing responsibility, an educational responsibility to help ourselves and those we come in contact with, to understand the situation, not only in Central Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East, but also here at home. And that’s what this roundtable is dedicated to.

Hiromi Lorraine Sakata

I don’t know exactly how to present my thoughts on music, politics, and violence to you today. I thought I should begin by telling you a little bit about the traditional place of music in Afghanistan, then go on to the current place (or, I should say, non-place) of music in Afghanistan today under the Taliban. Finally, I will talk about how the events of September 11 have affected particularly the music of Afghanistan, and music more generally, particularly how it’s affecting us here, very close to home, at UCLA.

Traditionally, music in Afghanistan was always considered a central form of cultural expression that was inextricably tied to a sense of identity. Music provided a form of communication which paid very little attention to political boundaries. So, it provided a means to promote intercultural understanding. You find many regions in Afghanistan where the music of one group of Afghans is very similar to, or the same as, the music of their neighbors across the border; they share a musical language, they share musical instruments, and they share musical repertoire. And so in this sense, music is very fluid, like water where there’s no dam. I think that’s what the present regime in Afghanistan is trying to do next, to dam up this music.

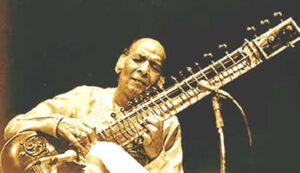

Because of music’s fluid properties, musicians are often able to act, or function, as cultural ambassadors. Let me just give you a couple of examples of how musicians were able to act as cultural ambassadors. One of India’s greatest sitarists, Ustad Vilayat Khan, used to travel to Afghanistan regularly during the regime of King Zaher Shah. He would perform there for the court, for the king, and also teach the king’s family music, the classical music of India—basically North Indian or Hindustani music. And so, you’ll find that there’s a sharing of musical appreciation for this kind of music.

are often able to act, or function, as cultural ambassadors. Let me just give you a couple of examples of how musicians were able to act as cultural ambassadors. One of India’s greatest sitarists, Ustad Vilayat Khan, used to travel to Afghanistan regularly during the regime of King Zaher Shah. He would perform there for the court, for the king, and also teach the king’s family music, the classical music of India—basically North Indian or Hindustani music. And so, you’ll find that there’s a sharing of musical appreciation for this kind of music.

Ustad Vilayat Khan was not the only musician who traveled back and forth; in fact, I’ve met many very famous musicians today who remember fondly their trips to Afghanistan to perform there for the king, and how royally they felt they were treated. Another example of a kind of musical ambassador was Ustad Mohammad Omar, who has since died. He came to the United States to teach the students of the University of Washington, and during his tenure, he was to give a concert—he plays a very traditional Afghan instrument known as the rabab, and he needed tabla accompaniment. Since we could not find an Afghan tabla player, we called on Zakir Hussein, who happened to be in the San Francisco area at that time. He very kindly consented to come and perform in the concert with Ustad Mohammad Omar. Now, Ustad Mohammad Omar did not speak English, Urdu, nor did he speak Hindi; Zakir Hussein did not speak Farsi, nor did he speak Pashto. Yet, these two musicians met for the very first time on the day of the concert, and through their understanding of a common musical vocabulary, they rehearsed and performed one of the most memorable concerts in my experience. Such exchanges have constantly taken place.

In terms of what is happening now in Afghanistan, under the Taliban regime they are in fact trying to displace music in Afghanistan. Mainly by censoring and banning music, the Taliban regime is attempting to starve and eventually kill the people’s cultural heritage. They attack it politically and violently: by issuing government decrees against music, by sending out religious squads (police squads) to find public performances and to break them up, and by destroying musical instruments—not only musical instruments, but also taped recordings and videocassettes. They have the power to arrest and punish musicians, as well as those who listen to this kind of music.

The West views this ban on music as a deprivation of basic human rights. In other words, the West feels that denying music is a denial of cultural expression, just as denial of a woman’s right to an education, to work, to participate in public life, are also seen as violations of human rights. I think this is what we’ve heard about the Taliban most recently.

How does the attack of September 11th have any bearing on Afghan music today? Well, there are many examples, but I’d like to give you a particularly poignant example that was reported in the New York Times last week. The article describes a young Afghan-American who was inspired to learn to play the rabab—the traditional Afghan plucked lute—after he heard about the Taliban’s attempt to ban music in his native country. He felt that it was his duty to keep his cultural heritage alive by becoming an Afghan musician himself. Yet, after the events of September 11th, this young man has not been able to play concerts, out of respect for the victims of the attacks. But also—I think more importantly—he fears that other Americans will see his musical performances as a celebration of these terrorist acts.

Now, this is a completely opposite view of how we in the West use music often to bring a community together, to bring them together to be able to mourn, or to remember; and, I think concerts are being organized all around the country in memory of the victims of the attacks on September 11th. For example, we, the Music Department and the School of Arts and Architecture, are organizing a memorial concert on December 8th at Royce Hall. If this is a concert, let’s say, of Beethoven’s music, everybody understands that this is a way of getting people together, to remember and memorialize. If it’s a concert of another kind of music that, perhaps, most Americans don’t understand—for example, a concert of Afghan music—then because of a lack of knowledge, we interpret that as having different motives. It’s not gathering together to mourn, but it’s more of a celebratory event; and, very frankly, most Afghan musicians or Middle Eastern musicians are afraid of the potential to stir up racial attacks against themselves. So, I want us to be very aware of the different perceptions. In the case of this young Afghan musician, the very act of defiance against the Taliban before September 11th was completely silenced after September 11th.

I have many more examples of how we’ve all been affected by the events of September 11th, but I’d like to just talk about two that directly affect us. I was looking forward to a concert by Youssou N’Dour, a Sengalese musician, who was supposed to perform for Royce Hall next week, next Thursday. I was just informed that the concert has been canceled, and it’s thought that Yousou N’Dour did not want to fly at this time. But I also imagine that the thought did cross his mind that we have not been particularly welcoming to international, foreign Muslim musicians. There are those who are afraid of what might happen. So, I think with that in mind, he decided to cancel his trip.

One last story: before September 11th, we were going to advertise the 40th anniversary of the Ethnomusicology Archives with a very colorful photograph of musicians in the field, musicians who had just been recorded and who are listening to their own recordings with very happy faces.

[shows picture]

It is actually a photograph of musicians in Rajasthan, India, photographed by Daniel Neuman, Dean of UCLA’s School of the Arts and Architecture, who does fieldwork in Rajasthan. After September 11th, we showed the photograph to a number of people whose gut reaction was: “Oh my God, you can’t use that! These men have turbans on.” And, “what are they listening to? Are they doing secret intelligence? And that instrument looks like a gun.” These musicians are musicians from Rajasthan, India, they are not Afghans, they are not terrorists, but people jump to conclusions. Needless to say, we did not use the photograph.

I just want to end by saying that information is very important. But, I think it’s more important how we use that information even in the best of times, and especially in bad times, when people’s emotions are so high and we’ve become afraid of anything we don’t quite understand—it is crucial to be sensitive to the ways we use our knowledge

Nazir Jairazbhoy

I think what I’d like to do, to begin with, is just to point out that the current situation is something like the movement of a ship that is too heavily weighed on one side, and that side—with the gravity, the misery, and everything else—puts things into perspective that life is not all lost: we’re still alive and we’ve a long way to go. One of the best ways of doing this is to introduce a bit of levity into the situation—that is the best approach to things, I feel. So, I thought I’d tell you a story, which I hope, tries to put the Taliban in their place. What I’m going to get at today is that the Taliban is trying to destroy music. But that’s not the first time that this has happened.

In India during the Moghul Empire the first emperors were very supportive of the arts, especially music, and helped support their development to a very high degree. Most Indian musicians today claim descent from the families of musicians during the sixteenth century. In the seventeenth century there was a Moghul emperor by the name of Aurangzeb (1658–1707 CE), and he decided to withdraw his patronage from all the arts. He thought the arts were frivolous, unnecessary, were misleading people, and guiding them into all kinds of horrible situations. So when Aurangzeb withdrew all the patronage that the musicians had been used to, the musicians decided to put on a parade.

They were walking along by the palace, and Aurangzeb asked, “What’s going on here?” His prime minister looked out and said, “Oh…I think it’s the musicians. They’re carrying a bier on their heads, and they’re saying that music is dead.” So Aurangzeb said, “Very good! Let them dig a really deep grave so that music will never raise never its head again.” Now we have music in India going even stronger than you can ever imagine it. So I say to the Taliban, “Remember what Aurangzeb tried to do and failed. You are going to fail, too, because music cannot be killed that easily. It’s a regular part of our beings.”

I have another story that is slightly humorous. It’s a continuation of Professor Sakata’s story about Vilayat Khan [pictured right], who performed in Afghanistan. I don’t know if you know much about Vilayat Khan, but there are a lot of stories about him—he’s a kind of legend in our time. Once, for instance, he is said to have found out in the middle of one of his concerts that there was a riot going on outside and that it would be unsafe for the audience to leave. So he kept playing—and playing and playing—until nine o’clock the next morning, just so that the riot could die down and it would be safe for the audience to leave. There are lots of stories such as that one.

instance, he is said to have found out in the middle of one of his concerts that there was a riot going on outside and that it would be unsafe for the audience to leave. So he kept playing—and playing and playing—until nine o’clock the next morning, just so that the riot could die down and it would be safe for the audience to leave. There are lots of stories such as that one.

This story about Vilayat Khan concerns Afghanistan, and I thought Lorraine Sakata might know the source. Vilayat Khan went to Afghanistan and performed for the emperor. The ruler was so thrilled by Khan’s performance that he said, “What to you want? What can I can I give you?”Vilayat Khan said, “Well, I want a Mercedes.” And the emperor said, “I’ve got about two hundred in my stables…just take which ever one you want.”

So good for Vilayat Khan, that was fine. Only when he took the car and it came to port in India, it wasn’t allowed to enter into the country because you weren’t allowed to have imported foreign cars at that time. So that car was stopped at the docks for two years! What finally happened was that one day Vilayat Khan was asked to go to perform in Nepal by the Indian government. The government was unsure about the culture of Nepal, and so they asked ruler in Nepal, “Who would you like to have?” And the ruler said, “Vilayat Khan.”

So they went to Vilayat Khan and said, “Please go and perform in Nepal.” And he said, “What about my Mercedes? It’s stuck there on the dock. What are you going to do about that? I’m not going to play for you unless you get that Mercedes through.” So, finally he got his car, and went and played in Nepal, and was a great success. [audience laughs]

Larraine Sakata: I have heard that story…

Nazir Jairazbhoy: You’ve heard it?

Larraine Sakata: Yes. [laughs]

Nazir Jairazbhoy: You think it’s true?

Larraine Sakata: Yes! [audience laughs]

Nazir Jairazbhoy: You have to know what’s true and what’s not true!

Music is a fabulous event in India, and the way that it is used is also fabulous. The problem is, of course, that everyone is now beginning to understand the power of music. So it isn’t only the “good guys” that are using music to break stereotypes, but the “bad guys” who are trying to use it to reestablish stereotypes by using music, in political campaigns, for instance. These political parties have songs, which are specially composed, which everyone starts singing. We don’t realize it, but what they’re doing is actually building up fundamentalist ideas, especially those used by the BJP [Bharatiya Jhanata Party]. They use songs to unwittingly preach against Islam by saying that: “India should be for Hindus and not for Muslims,” and so on. These songs, that certainly hint at these things, have a really big impact on society.

I’m a Muslim, but not a very practicing Muslim. Still, I feel that what is happening now is very interesting, because in Islam music is completely forbidden by the fundamentalists. Yet, if you go to Pakistan, you find that there are two kinds of musics, one of which is pop music. Now, it seems really incredible to me that you hear pop music blaring everywhere in Pakistan and in India, and Muslims enjoy it as much as everyone else; but the fundamentalists decry serious music—that is, classical art music. It is very strange that they should let the wild pop music go on, and all serious classical music is restrained.

Those who enjoy this serious music are usually labeled as “Sufis.” My experience is that the word “Sufi” is not really an absolute word. In my understanding, there are degrees of Sufism. There was a writer about twenty years ago, who wrote that seventy percent of the Muslims in India are influenced to some extent by Sufi ideas. Now what that really means is that we have a laity, (obviously there are practicing Sufis who are completely dedicated to their approach to life) a majority of people who are not practicing Sufis, but are influenced by some of their ideas. And one of the ideas is that music is the path to realization of God.

Now for myself, for instance, I am not a practicing Sufi (otherwise I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you—I’d be off meditating or whatever), but I’m very much influenced by their idea of music being a valid experience which is akin to my experience of God, whatever that might be. So there are many people whom I would call, “Muslim Sufis,” and there also many Hindus whom I would call “Hindu Sufis.” That is, they believe in some of the musical tenets of Sufism without having completely relegated their lives to that experience.

The Sufis have been using music for spreading their faith for centuries. And not only the Sufis: music in India is an extraordinary force because so many people there realize its value. Music is akin to humor. If you want to educate someone, start off with a funny story. That’s a common strategy in India with the traditional entertainers—they always throw in stories. Even priests will throw in humorous stories in the middle of their sermons, and they will invariably resort to singing. Some of the greatest saints are poet-saint-singers who composed poetry to be sung. They realized that to communicate ideas, you need music. And so music has been considered an integral part of society in Ancient India right down to the present time. Music can be used and misused—it can be used to break stereotypes, it can be used to create stereotypes.

This dramatic event that just took place in September has its repercussions in India, too. I’ll give you an example: in September of 1994 there was a plague in India in a place called Surat. Not long afterwards there were audio cassettes being produced by singers who sang about the plague and spoke about the people leaving Surat to look for another place to live. So, you have a dramatic event like this that has its terror, which is then picked up by performers and musicians. I shouldn’t be surprised when I go back to India that there’ll be songs about the “earthquake” that hit New York which has touched us all so badly. There’ll probably be songs about this act of terrorism. And when we do find them, we will record them and, we hope, bring them back to you to play for you the next time we come. Thanks.

Music Humanizing Our Visions: Reflections on September 11

Ali Jihad Racy

I would like to begin with an excerpt from the Prophet by Kahlil Gibran, a poet who came from Lebanon, the country where I was born:

And a woman spoke, saying, Tell us of Pain.

And he said:

Your pain is the breaking of the shell that encloses your understanding.

In the wake of the painful and utterly shocking events that occurred on September 11, we ponder as well as mourn. Those of us who study people’s musics and cultures may wonder about the relevance of what we do. We may doubt our roles or feel helpless and marginalized. However, I wish to propose that amidst a climate of violence, pain, and mistrust, the substance of our study can both uplift us and deepen our perceptions of ourselves and the world we live in—or, to quote Gibran again, break “the shell that encloses our understanding.”

Events of the magnitude we experienced on September 11 tend to intensify our feelings and reactions—that is understandable. This intensification may occur through the different phases we supposedly go through under such circumstances: namely, disbelief, shock, rage, grief, and finally reflection. As we look back, we notice that what happened in September led to bad stereotyping and, in some cases, to terrible hate crimes; but it also led to remarkable stories of compassion. During the few days following the attack, I hesitated to go out jogging—fearing insult, or even worse—for reasons that are beyond my own creation. However, I was also heartened by numerous phone calls from concerned friends, neighbors, former students, and fellow musicians. I am reminded of a story that I heard recently about a Native American grandfather who was talking to his grandson about how he felt in the wake of the recent tragedies. He said, “I feel as if I have two wolves fighting in my heart; one is the fearful, angry, revengeful one; the other is the compassionate, peace-loving one.” The grandson asked him: “Which wolf will win the fight in your heart?” The grandfather answered: “The one I feed.”

As an ethnomusicologist and Lebanese-American, I have tried to bring about a better understanding of a specific world region. Through my research on funeral laments in Lebanese rural communities, including my own village and birthplace, I know well how sadness affects people, how music and poetry enable human beings to cope and come to terms with their fragile existence. In my lectures on the role of music in Islamic mysticism, as represented by various Sufi sects, I have highlighted two underlying universal principles, namely, Unity of Being—or that holiness is in everybody, and Divine Love—or that love as a primary link between humans and the Divine, and among humans themselves. Similarly introduced in my lectures, is music’s transcendent power and its key role in achieving the mystical state; or, as the eleventh-century mystic al-Ghazali stated, its ability to soften the soul and cause it to yearn. Furthermore, in my various writings on secular Arab music, I have spoken extensively on tarab, the ecstatic state that music evokes in listeners, an aesthetic experience that seems both abstract and visceral.

In this country, the aftermath of the attacks prompted numerous noteworthy developments. As it seems, there has been a new interest in the world around us, as shown, for example, by the numerous television reports and documentaries on Islam and Muslims. Some books on the Middle East, especially on the Arab world, have been among the nation’s bestsellers. The media seems a bit more willing to listen to academic specialists, including those who have had direct experience with the cultures concerned. More individuals are becoming interested in global issues, and are trying to understand and critically assess our country’s foreign policy.

However, these events have also highlighted music’s role in our lives, and led to a certain discourse on the role of the arts at times of crisis. After the attacks in New York, National Public Radio interviewed the host of a music radio-program about listeners’ subsequent musical requests. In the interview it was made clear that music occupied a primary niche in listeners’ psyche, although for a couple days right after the attacks music programming was discontinued. Musical choices were both personal and subjective; yet, some patterns were obvious. For example, many requested music to fit their state of mourning—Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings was listened to again and again. Quite a few wished to hear Beethoven’s music, which they treated as a sort of prayer, while some listeners requested works by Mahler, among other composers. But others also found solace in Beatles’ songs, in jazz, and in various popular genres. Meanwhile, a special CNN report entitled “Terror and Art,” documented the arts’ focal position in the wake of the attacks. A female singer, Sherry Watkins, was interviewed about a song that, we are told, “just poured out of her the day after the terrorists struck.” The singer notes, “Those words didn’t come from me. They just came through me. I was just a gate.” Others interviewed in the report stress that artists are sometimes motivated by the most horrific occurrences. It is similarly shown that after the shock, school children expressed their feelings by painting the images they had seen repeatedly, a creative process that served an important cathartic purpose.

As I watched and heard recent broadcasts from the local media, and from the Middle East via satellite, I was interested in finding out what music does amidst the climate we are experiencing today. As I saw it, during the five weeks or so following the attacks, music operated on at least two broad and closely related levels. The first can be characterized, in general terms, as psychological transformation. The second follows the dictum of “e pluribus unum,” or “out of many comes one,” which underlies the repeatedly shown television advertisement in which members of different ethnic groups utter the expression, “I am an American!” in their own English accents and mannerisms of speech. On the first level, or that of “psychological transformation,” music addresses three emotional domains: a) mourning, or the exteriorization of the painful sense of loss or grief; b) the need to be emotionally uplifted or reconnected mentally and socially; and c) a sense of reassurance, recovery, and strength. On the second level, namely of “oneness in diversity,” music has been used to evoke an encompassing sense of “us”—as a union of diverse ethnic, religious, and cultural groups, and globally as a world community with basic ties and commonalties. In both cases, however, music’s efficacy stemmed not only from its acquired symbolic connotations, but also from its inherently flexible or even abstract message. In light of such flexibility and abstractness, musical expressions were often recontextualized, reoriented, and reinterpreted in creative and highly affective ways.

My observations are inspired by several music related highlights. In an official ceremony in London a few days after the tragedy, the Buckingham Palace guards, whose bright red uniforms contributed to their unmistakably British image, were ordered to play the “Star-Spangled Banner” before the British anthem as a gesture of support for the American people. [click here for Real Audio example.] Some Americans among the spectators wept, and as soon as the performance ended the tearful listeners applauded with tremendous enthusiasm. In a large outdoor ceremony that New York and its mayor organized as a tribute to the victims, the program presented a religious, ethnic, and artistic microcosm of our nation. Placido Domingo’s performance of Schubert’s Ave Maria was followed by a variety of presentations, including a call to prayer by an African American Muslim. The local musical mannerisms through which this religious expression was rendered, added to its symbolic significance. This was followed by chanting from the Qur’an, delivered by a Philippino reciter. The ceremony ended with Mark Antony’s “America the Beautiful,” a finale that roused dramatic enthusiasm, a surge of ecstasy that caused the thousands of flag waving spectators to rise in thunderous applause. By and large, this ceremony appeared to evoke both a sense of individuality within unity, and to create a gradual but dramatic feeling of emotional transformation.

Global statements were also made. For example, the use of U2’s music video “One” as a closing segment for a Larry King CNN program about a month after the attack, brought to mind a statement made by Bono (U2’s frontman) in Time Magazine: “Rock music can change things. I know it changed our lives. Rock is really about the transcendent feeling. There is life in the form” (53). U2’s music video presented a sound track accompanying a collage of some twenty-eight film shots taken in different parts of the world: including Washington, DC, Beijing, Tijuana, Marakesh, Tibet, Jerusalem, Cairo, Sidney, and ending in New York City. With such expressions as “We’re one, but we’re not the same,” and “You got to carry each other, One!” the text is set to a melody that seems symbolically fitting through its active harmonic movement and its consistent dynamic flow.

A comparable statement came from the Middle East. A short music video broadcast from a major Lebanese TV station in Beirut during the few weeks following the attacks, expressed sympathy with the American people. It displayed two separate small frames, subtitled “New York, 2001,” and “Beirut, 1982,” both captions superimposed upon the image of a flowing American flag. The two frames simultaneously showed black and white film scenes of the New York attack and of Beirut during the civil war, a few years following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. The graphic and strikingly shocking depictions of destruction and suffering victims in both frames were accompanied by an excerpt from “Fragile,” a song from Sting’s new CD recorded on September 11 and dedicated to the memory of the attack victims. We hear, “That nothing comes from violence, and nothing ever could. For all those born beneath an angry star, lest we forget how fragile we are.” The music video closes with the following written statement: “We are joined in sympathy for the innocent and in our condemnation of the deeds beyond imagining …” Underneath it says, “the People of Lebanon.”

Such musical manifestations allow us to understand the importance of music in our lives, even when we feel threatened, distressed, or alienated. Certainly, music can serve a wide variety of agendas. Examples from different historical periods and from contexts familiar to us today show that music is frequently used toward selfish, antisocial, and belligerent ends. Yet we also link music to aspects of our existence that are most universal and most human, including our fears and vulnerabilities, our hopes, and triumphs. In this latter sense, music can humanize the world’s visions of us, as well as humanize our visions of ourselves.

Questions

Audience member: In discussing the role of art and politics in times of war, one of the issues that we deal with is the fine line between art and music being a kind of place for solace and contemplation—that Professor Racy so nicely described in his talk—and art and music as a kind of vehicle that—I think a lot of times inadvertently—brings out nationalistic feelings regardless of which country it’s coming from. I find it interesting to see both these sides in the images that Professor Racy was showing. Would you talk about them a little bit more?

Racy: Music can serve so many purposes. The power of music is that it’s very abstract, and the abstraction of music lends itself to so many messages. Music becomes a double-edged sword, or weapon, that can stir emotions in different directions. But I think that there is an element in music that transcends the rhetoric and discourse that we indulge in here. That [transcendent] element shows a side of us that is very human, specifically when music brings out certain emotions. It’s very important to try to understand how people behave on that level; and how they use music to create a vision of themselves that’s very human. I think that vision gets lost in times of crisis, when you see people grieving or mourning. Music plays a very important role in this. It’s like seeing people suffer or experience pain. So we can actually understand music from this humanizing point of view.

Audience member: There is something that Lorraine Sakata brought up that I’d like each of you to address. We know that we are in a time of the condensation of symbols, so from our point of view—as people that study aesthetic expression—we work to understand the complexity and the multiple meanings that symbols have. We see, through what the media portrays and the various rhetorical positions that government officials are taking, that these symbols can become compressed and simplified into binary oppositions of “for or against.” The issue that Professor Sakata brought up of the photograph for the 40th anniversary of the Ethnomusicology Archives brings up many questions dealing with this simplification of the meanings of symbols—such as the turbans that the musicians were wearing in that photo. As teachers, researchers, and students, what kinds of positions do you think we can take to counteract when the manifold meanings of these symbols are being co-opted in a particular ways?

Sakata: We need to convey information so that people understand that a turban alone does not necessarily signify a terrorist, a Muslim, or a Middle Easterner. For example, you’ve heard in the news about the attacks on Sikhs simply because they wear turbans. At the same time, the timing for choosing the photo [for the Archive’s 40th anniversary] was so close to September 11th that we really didn’t want to press the issue. We didn’t have a forum or venue to really explain the picture, so we opted not to use it. We used another picture in its place: a picture of Peruvian children dancing, photographed by one of the ethnomusicology students. We did ask ourselves whether we were doing the right thing by pulling the photo of the turbaned musicians simply because we expected negative feedback for the wrong reasons, but in the interest of being sensitive to the heightened feelings and fears of the moment, we decided to choose another time and place (such as this forum) to address the issue of symbols.

Jairazbhoy: As teachers, we’re put in a difficult spot because, obviously, what we want to do is to teach people to be broad-minded, and to not have a narrow hatred for things that they are unfamiliar with, nor to make negative stereotypes. To encounter this…we go through a lot of fear. I do anyway. I would like to express myself to those people, but I’m scared. And I think that many of us are scared: we want to change society so that it’s broad-minded and looks at things in a rationalistic light. But do we want to be the ones to do it? That’s the question. Now, if I were thirty years younger, I might have considered it, but right now…[audience laughs].

Audience member: I think, Professor Racy, that you show very compellingly the role that music has in this time of crisis with your video examples. But, I’m wondering what is our role—those of us who are in the field of music and write about music—in the way these symbols are functioning in what’s going on right now?

Racy: I’m sure that some of us might have opinions about what to do with this material. Actually, I was interested in how symbols are used when I recorded these examples. That ties in with the question about the different meanings of symbols, not only in how symbols have certain intrinsic power, but the way we work with them and make them more effective. We put in them great power, an added dimension that we can read them contextually.

I was most fascinated by the footage of Buckingham Palace. Here we have a very well-known and powerful symbol, but look who’s playing…those guys with red hats, the British people who colonized us. The queen asked them to play the American anthem before the British anthem. The brass sound reminded me so much of London. So, look at the complexity of emotions that this musical manipulation brought about—and I don’t mean “manipulation” in a bad sense at all, but in an artistic sense. It brought tears, and at the end, applause. The reason I included the other video clip of raising the American flag to full-staff was to show that the same anthem was played, but what a difference in the mood or affect that event evoked. Both are legitimate, both are needed. But you have the same piece of music, the national anthem, played the first time with a certain carthatic effect and the second time with a sense of going back to business.

In all this I sense the human element in us wherever music goes to the depth of our soul—so often [music] gives back to us different images of ourselves, including the need for togetherness and of how fragile we are as human beings. I talked to friends who said, “you know life is a combination of good things and bad things, and you never understand it fully, but something like music keeps us going.” That goes to the heart of my talk. I’m exploring the idea that music is here one time doing one thing, and another time doing something else. And I don’t know if we have an answer to how that works. As educators and teachers, we try to understand how music can humanize our visions at times like these. I think that when people see other people feeling and singing, it communicates something other than just a political message.

Sakata: I’d just like to add another story about how music is  being used, not exactly as a symbol, but as a form of musical offering for universal understanding. This is a story that I heard from a friend who was just in London and happened to be watching a television show on Vienna. In this excerpt they showed the Vienna Boys’ Choir—but what were they singing? They were singing a song that was made famous by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan [pictured right] known as “Allah Hoo, Allah Hoo.” I thought that this was a way for the Vienna Boys’ Choir to reach out to say that this is good music, which represents Islam.

being used, not exactly as a symbol, but as a form of musical offering for universal understanding. This is a story that I heard from a friend who was just in London and happened to be watching a television show on Vienna. In this excerpt they showed the Vienna Boys’ Choir—but what were they singing? They were singing a song that was made famous by Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan [pictured right] known as “Allah Hoo, Allah Hoo.” I thought that this was a way for the Vienna Boys’ Choir to reach out to say that this is good music, which represents Islam.

|

Audience member: I just wanted to share story. I had been staying in a small town in New Jersey and I got a ride to the train station on September 12th. The gentleman who was giving me a ride to the station was a man in his sixties. We stopped at a full-service gas station, and the gas station had a lot of workers that were Arab and they were playing Arab music in the background. The gentleman that I was with got very, very upset and very angry. He yelled at the workers; he went and got the manager and yelled at the manager; he went and got the owner and yelled at the owner—all for paying Arab music on a day like that. He said that if they were going to play any music at all, that they should be playing Frank Sinatra singing “New York, New York.” I found this all very sad and surprising. Earlier that same morning I had seen the same gentleman display a huge American flag on his front lawn. For someone whom I never knew that music mattered to at all, the Arab music became this huge thing for him to hate, and hearing it made him really angry and upset with the whole culture that produced this music.

|

Audience member: We have heard from Professor Racy about the humanizing potential of music; we’ve also heard from Professor Jairazbhoy and Lorraine Sakata how Muslim fundamentalists damn music, de-humanize women, and they also sort of approved of the events of September 11th, which assumes a de-humanizing of the victims on the part of those that committed this crime. There seems to be some obvious trends of de-humanization within Muslim fundamentalism: what is the source of that? Is it the Qur’an, as they claim? Or is it something else?

Racy: Many scholars of religion agree that the beliefs of religions can be interpreted in many different ways. We only have to think back to the time of the Crusades—the eleventh through the thirteenth centuries—where people waged a war in the name of religion. Religions have everything in them. If you take things out of context, you can easily abuse them and violate the beliefs that counter these abuses. So I think instead of looking at any religion as an absolutely predictive force, many people examine religion for how it’s understood by people and how people use it. People use religion in many different ways—they also abuse it in many different ways.

Sakata: I just think that you have to be careful about using “fundamentalists” when you probably just mean the Taliban, which is a certain strain of Muslim fundamentalists who have their own interpretation of the Qur’an. I don’t believe that all “fundamentalists” dehumanize women.

Jairazbhoy: The answer to your question is both “yes” and “no.” There is some evidence in the Qur’an, especially in the saying of the Prophet, which suggests that you can use the evidence from one thing or the other. For instance, there is a reference to the fact that the Prophet Mohammed used to listen to wedding songs: therefore, you can say that music is okay. But they say that’s an exception since they don’t allow instruments, and so forth. You can take this contradictory evidence—if you take it out of context, as Professor Racy has said—and take one little bit and believe in it. So the question that you really want to ask is, Why do some people isolate from the Quern the things that they do? Why do they take all these negative things and put them forward? Why don’t they emphasize the other aspects from the Quern that speak about the brotherhood of man? My father was a writer who wrote about the Prophet Mohammed. My father was very extreme: in his eyes everything was fine. In the eyes of a fundamentalist virtually everything is bad. And I do use the word “fundamentalist” because there are some extreme ways of interpreting religion. As Lorraine has said, there are different types of fundamentalists, and there are fundamentalists in every religion. They are provocative: they talk about changing other people; they don’t apply their thoughts to themselves, otherwise they’d be fine. But fundamentalists believe that everyone should be doing as they are doing; that’s where the problem comes from. I don’t mind them believing whatever they want, but insisting that all women should wear purdah all the time…If they believe that, then good. But to force other people to do it….

|

Audience member: We’ve heard a lot in the media recently about the potential threat to civil liberties, particularly the potential narrowing of the expression of political dissent during this period of time when we’re expected to close ranks behind the government. I find that it’s interesting that music also comes under this threat of censorship. For example, there’s been a rumor going around the internet of a company that provides music going to radio stations that decided to put a unilateral ban on very specific types and pieces of music. For instance, it was reported that they said that you couldn’t play John Lennon’s “Imagine”; or you couldn’t play Simon and Garfunkel’s “Bridge Over Troubled Water”; and you couldn’t play anything by the group Rage Against the Machine. This rumor [has since been disproved as only a new urban legend, but this story] shows people’s fear of censorship, even where music is concerned. Music scholars are in the position where we try to help people understand the way in which music can open up the possible range of civic discussion. What can we do to prevent very powerful forces in society from closing down on this discourse?

Audience member: May I address this? I think that it’s very important to think about what Professor Racy pointed out earlier, that it’s very important to be very conscious of musical symbols and what they mean, and to try to work in a way that creates an environment where people can be free to interpret music in different ways. With music we have such a powerful tool that creates a wonderful space for people to be in. Music can be used in the most beautiful ways since it’s invisible. I personally think of that cello player in Sarajevo who demonstrated that music is really the most powerful way to show the spirit.

With music we have such a powerful tool that creates a wonderful space for people to be in. Music can be used in the most beautiful ways since it’s invisible. I personally think of that cello player in Sarajevo who demonstrated that music is really the most powerful way to show the spirit.

Audience member: I am from Sarajevo, and I know the guy that plays the cello. His name is Vedran Smailovic. [pictured right] He played on the street where, during the heavy bombardments, many people were killed. For us, he was a hero. But for the Serbs he was an idiot. His playing music at that critical period simultaneously had completely different meanings. I think that this problem of the many meanings of music very complex, not only in how we relate to music, but also to how music is affecting the people who are fighting against us. How can we overcome this breach, and what may we do to overpass this gap between these different musics? I think that this is the biggest problem: how not to hurt people through music; how to deal with those people who have opposing aesthetic and political views towards music.