Folk Grooves and Tabla Tāl-s

By James Kippen

The original version of this paper was given at the Toronto 2000: Musical Intersections conference on Thursday, November 2, 2000 as part of a panel on “Cultural Constructions of Time in South Asian Music Cultures.” I wish to thank the organizer, Richard Kent Wolf, other participants David Trasoff and George Ruckert, and discussant Lewis Rowell for their comments and contributions to this stimulating debate. I also wish to thank the Social Science & Humanities Research Council of Canada for an operating grant (#72005981) that helped make it possible for me to conduct this research.

Tāl (Sanksrit: tāla) refers both to the abstract rhythmic system found in the music theory of the Indian subcontinent and to specific metric patterns. Repeated cyclically, these metric patterns provide a stable framework for composition and performance. Their structural properties are marked by an ancient system of hand gestures which subdivide the cycle into segments of equal or unequal length and create an internal rhythmic hierarchy. Performers and audience members are often seen gesturing with claps and waves: the clap is produced by slapping the right palm down onto the left, or onto the thigh; the wave is, by contrast, a silent gesture in which the right hand moves away and turns palm-upwards, ending with a small bounce akin to a conductor’s beat that effectively marks the absence of a clap. By convention, claps are notated with a sequence of numbers, and waves are designated by a zero (0). However, the clap marking the all-important beginning of a cycle (sam) is usually accorded an X rather than the number 1.

The system of gestures is adhered to rigorously in the southern Indian classical system known as Karnatak music, and somewhat less rigorously in the northern Indian classical system known as Hindustani music. The modern performance traditions that now dominate Hindustani music are rooted in developments that occurred in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: khayāl singing (see Bonnie Wade’s comprehensive discussion of this genre, 1984), and the sitār and sarod instrumental traditions (see Allyn Miner’s seminal work, 1993). These are now routinely accompanied by the tabla drum pair, whose provenance can also be traced to the early eighteenth century. However, the tabla was originally used to accompany the lighter songs and dances of the tawāif-s (courtesans), and it gradually spread and rose in importance until it finally supplanted the older and more austere pakhāvaj (double-headed barrel drum) as the pre-eminent drum of Hindustani classical music by the end of the nineteenth century. It is my contention that the main reason the clapping gestures are less rigorously adhered to in this music is that the metric-rhythmic system of the upstart tabla is in many ways incongruent with the older system of tāl that is preserved in the pakhāvaj drumming tradition. By contrast, the tabla’s drumming patterns are largely indebted to folk, light, and semi-classical rhythms and meters that follow different rules. I have characterized these rhythms as grooves, by which I mean regularly repeating accentual patterns rooted in bodily movement (i.e. dance).

Modern Indian scholars and performers of Hindustani traditions, particularly those who have come to it as a vocation and not as an hereditary occupational specialization, have often promoted a revisionist interpretation of the music: one that emphasizes its ancient Hindu roots, its spiritual and intellectual properties, and its solid theoretical sophistication. The remarkable yet unpublished dissertation of Rebecca Stewart (1974) was the first to challenge this view by investigating ṭhekā-s: the fixed accompanimental patterns played by the tabla. I intend to build on this work by peeling away some of the layers to expose the true nature of tabla tāl-s. What is revealed, I think, has implications for the retelling of Hindustani music history.

The Concept of țhekā in Relation to the pakhāvaj

Metric cycles are found in the northern Hindustani system as well as in the southern Karnatak system, but only in the first are they articulated by a fairly fixed series of bol-s, or quasi-onomatopoeic syllables with corresponding drum strokes (e.g. dhā ge nā tira kiṭa etc.). When repeated cyclically these syllabic/stroke patterns are known as ṭhekā, meaning “support”: an appropriate word in view of their essential function as supporting or accompanying patterns. Among traditional (that is, hereditary) Hindustani musicians I have found that the ṭhekā is the primary signifier of a tāl, not the clapping pattern. Since no equivalent fixed pattern exists in Karnatak music the gestures dominate there, often to the extent that a knowledgeable audience joins the musicians in unerring sequences of claps, waves, and finger counts. This is rarely the case with a Hindustani concert. The difference, then, is that Hindustani meter is an internal notion that is externalized by the ṭhekā while Karnatak meter is an internal notion that is externalized by clapping.

The notable exception in Hindustani music is dhrupad, which retains much of its gestural language: in this older, and now much rarer, genre accompanied by the pakhāvaj there was almost certainly no concept equivalent to ṭhekā, and the early twentieth-century scholar V.N. Bhatkhande’s invented term thapīyā has no currency (I have never heard it used). As is the case in Karnatak music, Hindustani dhrupad singers and pakhāvaj drummers perform compositions and improvisations simultaneously, and so rather than repeated cycles of fixed bol patterns it is the hand gestures that provide (i.e. externalize) the necessary temporal markers. It seems likely that both the concept and the practice of ṭhekā, if not the term, were borrowed by the pakhāvaj in recent times. Bol patterns associated with traditional pakhāvaj tāl-s (e.g. tīvrā, sūltāl, cautāl)[1]am aware that there is no universally-accepted version of a ṭhekā for any tāl in tabla or pakhāvaj playing. There are stylistic differences between the various performance traditions, and tempo … Continue reading are really adaptations or extensions of a short paran (composed sequence) that ends with a standard cadential figure tiṭe katā gadī gena. As markers of the internal structure of the tāl-s these patterns are inconsistent, otherwise the position of the claps (X, 2, 3 etc.) and waves (0) would have more in common. (Note, in particular, that tiṭe katā gadī gena is marked by a clap and a wave in sūltāl and by two claps in cautāl). I would like to say that these pakhāvaj bol patterns qua ṭhekā-s have probably become fixed by a mixture of habit and the scholarly (and/or modern didactic) practice of writing them down, but more evidence is needed.

Pakhāvaj tāl-s are thought to be linked to Sanskrit verse whose agogic organization is essentially an additive, or quantitative, system of short (S) and long (L) syllables: the short, marked as a clap, is half the duration of the long, marked by a clap plus a wave. In this system, though, each clap and wave in sūltāl and cautāl is given its own vibhāg, or subdivision. Tīvrā is clapped and played as 3+2+2, but is rationalized as 2+1+2+2, or LSLL. Dhammār (or horī dhammār, a fourteen-count[2]I defer here to Harold Powers who recommends the use of “counts” instead of the more commonly-found “beats,” since the latter may be more usefully reserved for “metrical … Continue reading tāl whose constituent bol-s and structure are hotly debated, is an exception that can be explained by the fact that it was borrowed from the folk music of the Mathura region (the homeland of Lord Krishna).

The Problem with Tabla tāl-s

For all genres other than dhrupad it is the tabla (two-piece tuned drum set) that is Hindustani music’s indispensable time-keeper. Popular and scholarly texts (e.g. the widely-found Tāl Prakāś) and manuals list dozens of tāl-s and ṭhekā-s most of which are rarely, if ever, performed outside of an artificial context. The Bhatkhande Sangeet Vidyapith tabla syllabus,[1]The Bhatkhande Sangit Vidyapith is a prominent affiliating and examining body that also prescribes degree syllabuses and course texts. for example, expects a working knowledge of, among others, “Shikhar, Rudra, Yati Shikhar and Chitra” and “Basant, Brahma, Laxmi, Vishnu, Ganesh and Mani.” Taranath Rao’s Pranava Tala Prajna (Feldman 1995) lists, in addition to several common and not-so-common varieties, 101 obscure tāl-s ranging from two to thirty-five counts. All painstakingly notate the sam (the beginning of the cycle, with an X), vibhāg-s (subdivisions), tālī-s (claps), khālī-s (waves), and mātrā-s (counts). One purpose of this seemingly perverse interest in tāl esoterica is, I think, to vindicate the tabla as an Indian instrument with a quintessentially Indian theory, terminology, and repertoire rooted deeply in a Hindu past. Since the tabla has traditionally been played almost entirely by Muslim hereditary specialists, the socio-political significance of this revisionary change in focus becomes obvious, particularly in the context of an increasingly Hindu nationalist India following Independence.[2]I am aware that considerable interest in diverse tāl-s exists in Pakistani Punjab, perhaps because the pakhāvaj featured prominently in the recent lineages of tabla players in and around Lahore. … Continue reading

Although the late-twentieth century has seen an increasingly large number of tāl-s in use, the tabla’s traditional role of accompaniment was carried out with just a few of them and its solo repertoire was, for the most part, set in just one: tīntāl. The semi-classical ṭhumrī/dādrā and classical k͟hayāl vocal genres have repertoires of compositions in various tāl-s of six, seven, eight, ten, twelve, fourteen, and sixteen counts. Instrumental music, according to Ravi Shankar, only began exploring beyond the boundaries of tīntāl as a result of innovative gat-s (compositions) introduced by his teacher Alauddin Khan in the early part of the twentieth century. Shankar himself added more, often using tāl-s with odd numbers of counts (nine, eleven, thirteen, fifteen) and even fractions (Shankar 30).

Scholars continue to puzzle over the incongruities of the Hindustani tāl system. Why does seven-count rūpak begin with a wave instead of a clap? Can the sam in rūpak also be the k͟hālī? Why does a “dhā” occur on the ninth count in tīntāl when the structure suggests a “tā,” and, conversely, why is there a “tā” on the thirteenth count when one expects a “dhā“? (See Erdman 23.) Why does the ṭhekā of twelve-count ektāl seemingly defy the internal divisional structure of the tāl? And why does ektāl have two k͟hālī-s? As Joan Erdman found (ibid.), there is little to be gained from asking traditional musicians since they tend to accept uncritically the knowledge they inherit from their forefathers. Among writers it is common to offer the ready excuse that lakhşaṇa (theory) simply lags behind lakhşya (practice) (Ramanathan 15). But most modern theory, in my view, suffers from an inability to problematize Hindustani tāl and an unwillingness to relate it to the sociocultural milieu in which this system emerged.

The answer to these tāl puzzles at the broadest level, I would suggest, is that Hindustani tāl has developed organically from the rhythmic characteristics of a range of folk, popular, and semi-classical genres, and it simply does not fit the classical theoretical model for rhythm and meter. Effectively, the rhythms of these other genres, or grooves as I like to characterize them, have largely been superimposed on existing metrical frameworks derived from Sanskrit verse. This idea is not new: Rebecca Stewart has made a splendid case for this view, and Peter Manuel’s excellent work on the ṭhumrī has provided evidence that this most influential of genres used folk-derived rhythmic structures.

From Folk to Classical: The Emergence and Rise of the Tabla

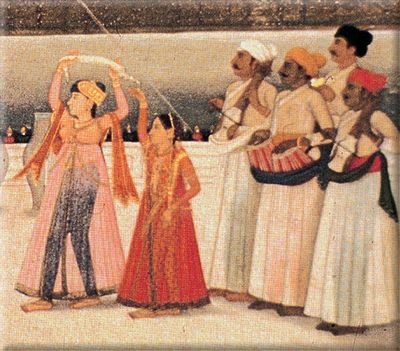

Through a combination of pictorial and genealogical evidence Stewart has argued that the tabla emerged in the second quarter of the eighteenth century, probably in the Punjab hill chieftaincies. Genealogical evidence further suggests that the tabla was the domain of a caste of bards known as Ḍhāṛhī (also Ḍhāḍhī, Ḍhārī who came from the region of the Punjab and Rajasthan (see Bor 60-2); for centuries they had used drum (ḍhaḍ) and fiddle (sāraṅgī) to accompany songs that documented the genealogies and praised the heroic feats of their patrons. Like Ḍhāṛhīs before them (they are mentioned in Abu-l Fazl’s Akbar Nama of the late sixteenth century) these early tabla drummers migrated to larger and richer centres of patronage, the ultimate source of which was the Imperial Mughal capital, Delhi. It was to there and to about 1750 that we can trace the first identifiable member of the Delhi lineage of tabla players, Sudhar Khan. For the next fifty to seventy-five years we note a steady increase in the portrayal of the drums, which were usually played standing, bound waist-high in a cloth.

A drummer’s passport to the courts was through the entourages of the tawāif-s, the courtesans of North India who were experts in the arts of dancing, singing, poetry, and love. Owing to the socio-political demise of Delhi in the late eighteenth century many courtesans and their troupes migrated to other centres of patronage, most notably Awadh (also Oudh or Oude) to the east. Awadh’s capital, Lucknow (from 1775), soon emerged as the new seat of Hindustani culture, and wealthy navāb-s (viceroys) and their courtiers helped create a fertile environment for the emergence and development of so many forms and styles of music that we know today (see Kippen 16-26). In Delhi courtesans had specialized in performing the light and popular Urdu gazal and Persian reḵẖtā but in Lucknow they turned to the newly emerging, sensuous and often erotic ṭhumrī: a genre with strong folk roots (sung mainly in the rich and colorful Braj dialect of the Mathura region) that promoted a different kind of expressive musical language in which the tabla would come to play a significant role. The ṭhumrī was performed with accompanying dance gestures that illustrated and intensified the meanings and sentiments of the texts. Rather than the athletic, twirling, highly-choreographed kathak of today, eighteenth and nineteenth-century descriptions suggest that these dances were more physically-restricted and comprised subtle gestures and characterizations: for instance, the lilting, seductive walk of a woman shyly lifting her veil to allow her lover a glimpse of her face. These affective, interpretive aspects of dance are known as abhināya in modern kathak.

The tabla’s function in the dancer’s ensemble would therefore most likely have been to provide the same type of rhythmic accompaniment traditionally given by the naqqāra (hemispherical clay kettles played with sticks) and especially the ḍholak (barrel drum). It is not surprising, therefore, that despite the tabla’s clear organological endebtedness to the pakhāvaj (structurally the tuned head was identical, and the cylindrical wooden bass drum even used a temporary spot made of dough, as it still sometimes does in the Punjab) it began to take on physical aspects of the naqqāra by replacing the cylindrical wooden bass drum with a small hemispherical clay kettledrum. Moreover, tabla strokes and patterns were heavily influenced by the naqqāra and the ḍholak (Stewart 22-73). Naqqāra strokes differentiated effectively between high and low pitch levels (tā/ge), timbre (tā/Tin), resonance (Tin/tit), and stress (tā/nā), with pitch and stress being dominant (see Stewart 36-8 & 97). The ḍholak‘s great gift to the tabla was the flexible-pitch bass drum technique which added a richly-modulated, almost vocal inflection. The beauty of the tabla, and one of the most persuasive reasons for its rapid rise to prominence, was that it could mimic effectively the sounds, and therefore the repertories, of all other drums of the period, including the pakhāvaj.

The Divisive and Qualitative Nature of Tabla tāl-s

There were two main kinds of ṭhumrī in the early nineteenth century: the bol-banāo ṭhumrī, which focussed on a highly flexible melodic interpretation of the text; and the bol-bāṅṭ ṭhumrī which specialized in rhythmic manipulations of melody and text. Whereas the popular gazal had more commonly been set in shorter structures of six (dādrā), seven (pashto) and eight counts (qavvālī, kaharvā), the tāl-s used for ṭhumrī compositions comprised mainly fourteen or sixteen counts. As Manuel has shown (145-52), little separates fourteen- from sixteen-count ṭhumrī tāl-s, and since performance practice used to favor their flexible rhythmic interpretation they may in fact have been one and the same thing. Confusingly, both are called cāṅcar or (latterly) dīpcandī, and jat is another word sometimes encountered.

Structural evidence suggests few differences between tāl-s of eight and sixteen counts. In essence they all move in pitch from low to high, or from bharī (full) to ḵẖālī (empty), and back again. The quality of fullness is conveyed by the presence of the bass drum, which is represented by voiced syllables such as the phonemes ga and dhā; emptiness is suggested by the absence of the bass, and the corresponding unvoiced syllables such as ka and ta. First, these are not additive structures but rather divisive, based on their internal hierarchy: all of these sixteen-count tāl-s could be, and indeed often are, counted as eight or four beats, and the eight-count varieties as four or two beats. Second, these are not quantitative structures but rather qualitative, based on the means they use to realize this: their variable pitch, stress, and timbral qualities can be seen to follow almost identical patterns of organization, which I have tried to show by vertical alignment. One notes the vibhāg-oriented changes in pitch, a strategy that highlights the tendency for the all-important ḵẖālī (the only surviving Arabic/Persian term among Sanskrit ones) to fall halfway through the patterns. When conceived as fours the final vibhāg prepares the return to bharī with a contrasting musical signal. Since greatest contrast is achieved through pitch differentiation, the fourth vibhāg often includes the return of the bass drum. Sometimes, too, contrast is conveyed by density: a cadential flourish of more rapid strokes.

The folk/popular-derived kahārva and qavvālī might not look very much alike in all their details, but they do share certain structural properties: they move from bharī to ḵẖālī using sequences of bol-s that are almost identical in their pitch and stress contours. Their similarities become even more apparent when examined in relation to the slower dhamālī (dhamāl is a folk dance from Rajasthan/Punjab) which, it could be argued, combines the cadential features of both the others. In turn, dhamālī‘s relationship to the stately tilvāṛā (a hill fortress in the Punjab) and the primary ṭhumrī tāl of cāṅcar (cāṅcarī is a folk dance from the Punjab hills) is unmistakeable. Cāṅcar and ekvāi paṅjābī are really varieties of the same thing, but with different rhythmic emphases within the vibhāg: both disguise the pulse, especially when the former is played in the now extinct laṅgṛā (limping) style (see Manuel 149-50). The purpose of such rhythmic ambiguity is probably to accommodate irregular melodic phrasing through sensitive accompaniment, and an important contributor to this is the variable-pitch ghe stroke (Stewart 368). And thus one sees the connection between these tāl-s and paṅjābī, which also has the delightful name of “the donkey’s tail gaddhe kī dum kā tāl“: gad dhe kī dum — kā tāl —) mimics accurately elements of pitch and stress not immediately obvious in the notation.

The distinctly swinging, lilting paṅjābī tāl was one of the direct precursors of tīntāl, and even Bhatkhande referred to the latter as paṅjābī tīntāl (11). The other was known as dhīmā titāla, or simply dhīmā, and was notated by Imam in the mid-nineteenth century (190). The name dhīmā also appeared regularly on early twentieth-century recording labels, in fact much more so than the term tīntāl (see Kinnear 1994). Although dhīmā means “slow”, these early recordings show that its pace was what we would now think of as madhya-drut lay (medium-fast tempo): roughly 200 beats per minute. Recorded tabla accompaniments from this era show a strong tendency to integrate the rhythmic features and stroke patterns of both paṅjābī and dhīmā titāla. Fast tīntāl‘s indebtedness to dhīmā is undeniable, since it tends to use the recited phrase “nā Dhin Dhin nā” rather than the more cumbersome “dhā Dhin Dhin dhā” that is more suitable at slower speeds. Fast tīntāl also mimics effectively the “thā thei thei tat” tatkār (footwork) patterns of the kathak dancer. Fast tīntāl is nearly always reverted to at the conclusion of a ṭhumrī where, in the past, the singer and/or members of the dance troupe were expected to dance in quick tempo as the final refrain of the song was repeated.

Solving Some of the Modern tāl Puzzles

The reason tīntāl (literally, “three tāl“) is so called is because it was played in medium to fast tempo, counted as four beats, not sixteen: most commonly it would be marked by older musicians as “one, TWO, three, wave”, with the two falling on sam. The ninth count is not ḵẖālī in itself; rather it is the third vibhāg which is empty. Since each internal phrase is an anacrusis to the next metrically strong beat, the tāl might best be represented with its four symmetrical phrases. Further evidence for the validity of this representation is that, when reciting tabla compositions in quick tempo, many older musicians begin from count ten with the words: “Tin Tin nā nā Dhin Dhin nā.” The ṭhumrī was immensely important in the development of performance practice in other genres such as baṛā and choṭā ḵẖayāl and the instrumental gat traditions. (Rebecca Stewart’s doctoral work in this regard must surely be the most important unpublished exploration of the subject. See also the work of Bonnie Wade (1984), Allyn Miner (1993), and Peter Manuel). Tāl-s used for the bandish ṭhumrī (an extension of the bol-bāṅṭ ṭhumrī) such as rūpak, jhaptāl, and ektāl, soon found new and extended applications.

Ektāl, which Stewart has characterized as a catch-all term for several classical and folk rhythms (1974: 96), has superimposed a swinging, sesquialtera (or hemiola) pattern onto the agogic framework of cautāl. Its ṭhekā suggests that it is really best understood as four groups of three, in keeping with many of the melodic structures created for it; as such, its tālī/ḵẖālī structure mirrors that of the 16-count tāl-s. Argued in this way, ektāl has only one ḵẖālī; cautāl of course has none, because waves in the agogic system of long and short syllables are not ḵẖālī-s per se.

Rūpak has superimposed the popular/folk rhythm from the Northwest Frontier known in India as pashto (but also, sometimes, as the Pakistani-Afghan mūglai—the term rūpak is virtually unknown in Pakistan) onto the agogic framework of tīvrā probably in very recent times (compare this with Bhatkhande’s version from the early twentieth century). Because of pashto‘s characteristic lilting iambic movement from unstressed to stressed, and from high pitch to low pitch, the ambiguity of rūpak‘s sam becomes an issue (is it notated as a tālī or a ḵẖālī?; and if the latter, then why are the subsequent tālī-s conventionally-notated as 2 and 3 instead of 1 and 2?).

Conclusions

I have tried to show how Hindustani music has undergone a sea change in temporal thinking, from agogic Sanskritic verse meter to quite different divisive, qualititive structures marked by fixed patterns that emphasize pitch and stress. Stewart emphasized the likelihood of links with the Arabic system through the naqqāra drum tradition, and while I would not dismiss this view, I suspect that ample evidence for a different kind of rhythmic/metrical thinking exists in folk models drawn from the tabla heartland of the North and Northwest of the Indian subcontinent. Dhrupad’s dhammār is a case in point. Such a principle will come as no surprise to scholars of Karnatak music, since the common cāpu tāla-s are themselves derived from folk sources, quite unlike the primordial seven tāla-s (Nelson 2000: 144). There will be resistance to this view from those who would like to think that the tabla and its tāl-s are ancient and neatly accounted for by theory; they will likely feel uncomfortable when challenged with the notion that its rhythms emerged organically from the songs and dances of a category of women modern society now brands as disreputable.

Much more could be said, especially about tāl-s like jhaptāl and jhūmrā that, I would argue, have adapted (doubled) 2+3 and 3+4 folk-derived patterns to fit the standard four-vibhāg tālī/ḵẖālī format already described for sixteen-count tāl-s (and probably also for the twelve-count ektāl). More could be said also about the modern tendency to drive tempi to the extremes of the continuum, thereby altering the character of many of these tāl-s. That is a long story that will be the subject of future studies. One of the casualties for the tabla has been the loss of opportunity to swing and sway with the medium-tempo grooves of the folk, popular and semi-classical ṭhumrī genres: rhythmic realizations of the seductive, sensuous and erotic body and hand movements of the courtesan. Indeed, it mirrors the immense loss to Hindustani music culture of the courtesan herself.

Contributor

James Kippen studied Social Anthropology and Ethnomusicology under John Blacking and John Baily at Queen’s University, Belfast. His primary research in Lucknow, India, dealt with tabla drumming in its sociocultural context, particularly as interpreted by his teacher, the hereditary master Afaq Hussain Khan (1930-90). He is currently engaged in research into cultural concepts of time in Indian music and society, and he continues to study and practise tabla. Kippen is Professor of Ethnomusicology at the University of Toronto.

Works Cited

Bhatkhande Sangeet Vidyapith. Prospectus & Syllabus, 1981-1983. Lucknow: Citizen Press, 1981.

Bhatkhande, Vishnu Narayan. Kramik Pustak Malika. Parts 5 & 6. Hathras: Sangit Karyalaya, 1983.

Bor, Joep. “The Voice of the Sarangi: An Illustrated History of Bowing in India.” National Centre for the Performing Arts, Quarterly Journal, 15.1, 3 (September & December 1986), 16.4 (March 1987).

Erdman, Joan. “The Empty Beat: Kẖālī as a Sign of Time.” American Journal of Semiotics, 1, 4, pp.21-45, 1982.

Feldman, Jeffrey. The Tabla Legacy of Taranath Rao: Pranava Tala Prajna. Venice, CA: Digitala, 1995.

Imam, Muhammad Karam. Ma’dan ul-mūsīqī (In Urdu.) Lucknow: Hindustani Press, 1925. [The original MS, lost, dated from the late 1850s or early 1860s.]

Kinnear, Michael. The Gramaphone Company’s First Indian recordings, 1899-1908. Bombay: Popular Prakashan, 1994.

Kippen, James. The Tabla of Lucknow: A Cultural Analysis of a Musical Tradition. Cambridge University Press, 1988.

Manuel, Peter. Thumri in historical and Stylistic Perspective. Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1989.

Miner, Allyn. Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Wilhelmshaven: Florian Noetzel, 1993.

Nelson, David. “Karnatak Tala.” Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. New York: Garland, pp. 138-61, 2000.

Ramanathan, N. “The Changing Concept of Tala in North India.” Unpublished paper delivered at the International Symposium of the History of North Indian Music 14th to 20th Centuries. Rotterdam, 1997.

Shankar, Ravi. My Music My Life. New Delhi: Vikas Publishing House, 1969.

Sharma, Bhagwat Sharan. Tāl Prakāś (In Hindi. 7th edition, ed. Lakshminarayan Garg.) Hathras: Sangeet Karyalaya, 1981.

Stewart, Rebecca. “The Tabla in Perspective.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation: University of California, Los Angeles, 1974.

Wade, Bonnie. Khyal. Cambridge University Press, 1984.

ul-Zamān, Badr. Tāl Sāgar. (In Urdu.) Lahore: Idāra Farug-e-Fann-e-Mūsīqī, 1991.