Mandela’s Inaugural 46664 Mega-Concert – A Second Long Walk to Freedom – Sounding Out Narratives of Empowerment, Religion and Public Health at Queen, Bono, and Nelson Mandela’s Campaign Launch Concert to Combat HIV/AIDS

By Jeffrey W. Cupchik

Abstract

The first annual 46664 Campaign mega-concert event took place in Cape Town, South Africa, on November 29, 2003, launching Nelson Mandela’s 46664 Foundation and his new movement offering public health education on the prevention of HIV/AIDS. The event was broadcast to over two billion people and hosted “A-list” artists and celebrities Mandela had invited to the event. This paper examines the strategic use of the mass-mediated, multi-genre, mega-concert in the context of the launch of the 46664 Campaign, focusing on how the overarching narrative created a space within which several new songs were composed for, and performed at the occasion. The event exhibited a diverse program both musically and thematically, reflecting the campaign goals in several ways. To contextualize the sociopolitical, cultural, and musical importance of the inaugural 46664 mega-concert, the event is first placed in historical perspective with the renowned globally televised mega-concerts that preceded it (in Wembley Stadium in 1988 and 1990), held in Nelson Mandela’s name during the anti-apartheid movement. Second, this paper illustrates the ways in which this mega-concert exhibits strong thematic and musical continuity in connection with moral, religious, and spiritual values, and follows a dramaturgical narrative related with the message of the 46664 Campaign. Third, the paper explores how the event narrative champions Mandela’s legacy of struggle, empowerment, courage, and leadership, which, in turn, impacts and reflects the concert narrative and campaign strategies.

“Mandela, whose life can be characterized by the singular fight for justice through political action, has come to the correct conclusion that AIDS is not a medical condition, it’s a political one. And that the only way that this scourge can be defeated is by concerted political action.”

~ Bob Geldof, inaugural 46664 Campaign Launch Mega-concert, Cape Town, South Africa, 2003.

“Africa has a bad image around the world: AIDS, poverty and war. One thing that is really positive is Mandela’s fight to get these people up. Every time I see Mandela, every time people see Mandela in Africa, they really want to say, ‘Hey, listen, look, these are positive days!’ I think he’s a symbol.”

~ Youssou N’Dour, Senegalese recording artist, 46664 Campaign Launch Mega-concert, Cape Town, South Africa, 2003.

This paper is situated at the intersection of popular music studies, historical ethnomusicology, mass media studies, religious studies and public health studies, and focuses on the inaugural 46664 Campaign launch mega-concert in Cape Town, South Africa.[1]I would like to express my gratitude to those who read and commented on earlier drafts of this article: Rob Bowman, James Kippen, Ralph Locke, Sarah Morelli, David Mott, Marc Papé, and Kacie Morgan, … Continue reading It explores how the concert narrative was realized at once through: (1) consistent thematic refrains to the message of educating and empowering individuals to act responsibly in terms of their sexual health; and (2) creativity in terms of the musical setting of the number 46664 to deliver this message. “46664” was Nelson Mandela’s prison number, which he lent to the cause of this Campaign to address the HIV/AIDS crisis with his expressed purpose that “no one should be reduced to a number.” This reclaimed number “46664” (voiced as: “four, double-six, six four”) was arranged and set musically in several inventive ways by Queen, Beyoncé, and Bono/U2, together with the Soweto Gospel Choir and several other renowned African artists at this multi-musical genre event. This paper also pays close attention to (3) discursive consistency in the dramaturgical narrative (after Erving Goffman), calling attention to how certain themes (social responsibility and sexual health) are linked to religious/spiritual faith and girls’/women’s decision-making power regarding condom use. In addition, this paper explores the ways in which this mega-concert event exhibited (4) collaborative artistic endeavors in public performance, exemplifying the ideals of “unity,” Amandla, ubuntu, and community support.[2]The Nguni word ubuntu reflects the humanist philosophy espoused by Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The term is often translated colloquially as “I am because you are.” Archbishop … Continue reading

Finally, (5) visually the mega-concert was site-specific. The image of the Cape Town stadium at night lit up by the venue lights illuminating the mega-concert stage and the lights on Robben Island—seen in the same wide shot—conflated the past with the present and was perhaps regarded by some as symbolizing the possibility of overcoming the immediate crisis.[3]The Cape Town concert stadium venue is in view of Robben Island, just off the coast, where Mandela was a political prisoner for 18 years of his 27-year sentence. The visual message here conflates … Continue reading This image was projected onto a large screen at the back of the concert stage, and webcast/ simulcast to television and computer screens in the homes of an estimated two billion people globally while the concert narrative would primarily address the healing needed locally.

Education through Entertainment

Nelson Mandela’s 46664 Campaign slogan was simple, but telling: “awareness and education through entertainment.”[1]See the 46664 Campaign slogan on the homepage of 46664 <https://www.46664.org/za> which now takes you to <www.nelsonmandela.org>. Fighting the HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa and around the world requires a grassroots strategy that connects to youth—the population most at risk of contracting and spreading the virus. Focusing on educating youth was a key part of the rationale behind the goal of staging annual mega-concert productions that showcased popular “A-list” celebrities who garnered media attention, and became part of a multifaceted campaign strategy.[2]Among the many strategies utilized, all the artists consented to become 46664 ambassadors. See this article on Annie Lennox’s website regarding the fifth 46664 mega-concert in 2007 held in … Continue reading The combined goal was to change social attitudes and promote preventive health practices in order to respond constructively and effectively to one of the most serious global public health crises through education campaigns. Given that youth are the most exposed population, and South Africa the country most adversely affected, it was believed that celebrity endorsements from Nelson Mandela and “A-list” recording artists at live broadcast concert events could be used to sway public opinion about social and sexual practices. With its launch mega-concert in 2003, the 46664 Campaign mega-concerts became a platform for helping South Africans, and others around the world, to address artistically the HIV/AIDS crisis in ways that were populist and inspiring rather than alarmist and frightening.

Thus, in the same way that the transnational anti-apartheid campaign in the late 1980s and early 1990s became relatively successful in combating cynicism and histories of violence through instrumentalizing song, music events, and broadcast media, so too, the fight against the scourge of HIV/AIDS may yet be a battle waged strategically through a media campaign that alights music events and songs in inspiring ways to engender new sexual and social health practices.[3]Gregory Barz and Judah Cohen also note the interwoven links between the “A-list” artists and the international movement to address the AIDS crisis, and how Eurythmics’ Dave Stewart and … Continue reading Nelson Mandela’s persona of determination and heroism was situated at the center of this campaign, as he called for a global movement founded on a strength borne of courage to face this historically challenging obstacle.

A Mega-concert to Launch a Health Campaign; A Movement to Address a Crisis

In this paper, I examine the strategic use of the mass-mediated, multi-artist, and multi-music genre mega-concert event organized around the launch of the 46664 Campaign, and the new songs composed for the specific occasion. To address the sociocultural, health, and musical importance of the inaugural Cape Town concert, I first place it in historical context with globally televised mega-concerts in Nelson Mandela’s name that preceded it; second, I show the ways in which the concert exhibits strong thematic continuity, and follows a dramaturgical narrative precisely related to the message of the 46664 Campaign; and third, I look at how the event champions Mandela’s legacy and his ideals which, in turn, impacts the concert narrative and campaign strategies. The concert is also discussed in context with other mega-concerts in this multi-artist performance genre while focusing on how this inaugural concert centered on health education through religion/spirituality and popular music cultures.

The Cape Town mega-concert and campaign launch hosted “A-list” artists and celebrities Mandela had invited to the event: Oprah Winfrey, Beyoncé, Bono, Bob Geldof, Queen, Eurythmics (Dave Stewart and Annie Lennox) and several African and South African artists including Angelique Kidjo, Youssou N’Dour, and Yvonne Chaka Chaka. The event exhibited a rich program, both musically and thematically, reflecting the important campaign goals of health promotion and illness prevention in a number of ways.

Initially, it may be helpful to consider the seriousness of the health issue being addressed by the mega-concert. According to AVERT, an international AIDS charity, an estimated 5.7 million people were living with HIV and AIDS in South Africa in 2009 in a population of 50 million, more than in any other country.[1]“HIV and AIDS in South Africa.” 2010. AVERT. International Aids Charity. <https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa> (accessed February 27, 2019) National prevalence was around 11%, with some age groups being particularly affected. Almost one-in-three women aged 25-29, and over a quarter of men aged 30-34, were then living with HIV. It is believed that in 2008, over 250,000 South Africans died of AIDS.[2]Ibid

Mandela’s reframing the HIV/AIDS issue with the 46664 Campaign slogan “AIDS is no longer just a disease; it is a human rights issue” engendered strong support from the entertainment and business sectors who were interested in backing a high profile, transnational, mega-concert event broadcast globally.[3]Nelson Mandela, speech, “Launching 46664.” 46664 The Event, DVD, Disc 2. In 2003, Mandela traveled to London to launch the 46664 Campaign (www.46664.org). The issue, as he outlined it during the London press conference, was grave. Mandela spoke forcefully: “A tragedy is unfolding in Africa. AIDS today in Africa is claiming more lives than the sum total of all wars, famines, floods and deadly diseases such as malaria. AIDS affects people of all ages, but especially young people.”[4]Ibid Representatives from the 46664 Campaign partners—global leaders in the sectors of music television, Internet media, business, and technology–were on hand to deliver a message about their part in addressing the issue. Bill Roedy, President of MTV Networks International, gave the reason for MTV’s involvement: “fully one-half of new HIV infections occurs to young people every year. Tragically, that’s our audience.”[5]Bill Roedy, “Launching 46664.” 46664 The Event, DVD, Disc 2. According to Roedy, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) agreed to distribute the concert to 52 countries in Europe. The BBC agreed to air it on the radio in 13 different languages. The Asian Broadcasting Union (ABU) would distribute to 28 countries in Asia, and the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) agreed to run the show live. Roedy announced that the last time MTV did this, “we were able to generate 500 million households in addition to MTV.”[6]With Roedy and MTV’s corporate partners, the 46664 Campaign secured broadcasting rights in 166 countries, including broadcast dates on MTV and BBC of December 1, 2003, with an expected audience … Continue reading

“Nelson Mandela’s message is simple,” said John Samuel, CEO of the Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF), “All of us must care about the threat from HIV and AIDS.”[7]Mandela’s campaign is centered on research, prevention, and treatment—helping those who have HIV/AIDS to live in dignity while educating others about the means by which to prevent contracting and … Continue reading With 6500 people dying every day from the disease in Africa alone, and 9000 in total around the world, this campaign necessarily involves implementing a “simple” strategy on a massive scale. MTV Staying Alive recognized that the multi-artist mega-concert genre could play a powerful role in mobilizing youth, raising consciousness, and catalyzing participation in the 46664 Campaign to eradicate the disease.[8]See “The Media and HIV/AIDS: Making a Difference.” 2004. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. <http://data.unaids.org/publications/irc-pub06/jc1000-media_en.pdf> (accessed July 23, … Continue reading According to a UN report on the use of media in the HIV/AIDS crisis, “Education is the vaccine against HIV.”[9]MTV launched their Staying Alive campaign at the XIV International AIDS Conference, 2004.

Artists’ statements in the 46664 backstage interviews, on-stage endorsements, and introductions—but especially in the new songs written for the occasion—reveal a personal commitment to the cause of seeking humanitarian relief for those infected and affected by HIV/AIDS. Some of the “A-list” celebrity musicians Mandela brought to perform in his home country, South Africa, were those who had befriended him while championing his cause during the transnational anti-apartheid campaign more than fifteen years earlier.

Bob Geldof, who championed the famine-starved children of Ethiopia in late 1984 with his song “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” and then organized the Live Aid mega-concert in July 1985, was the first artist on the 46664 stage, and introduced the Cape Town concert with the following admission before playing Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song” on acoustic guitar:

The reason that we’re here is ‘cause a frail old gentleman who is one of the few giants of our planet has summoned us here, and you cannot refuse him anything. This is a man whose entire life is characterized by the pursuit of social justice through political action.

It is also the case that Mandela has been successful already in identifying a national-level injustice (the apartheid system), addressing it strategically with an international campaign, and overcoming it. The fight to raise awareness to effectively deal with the HIV/AIDS crisis is a cultural and political matter, after all, and the media is a powerful and necessary tool in any political campaign. Roger Taylor of Queen, one of the main organizers of the Cape Town concert, explained the role of artists as follows:

We’re just musicians using what we do as a platform to raise awareness effectively. And if you get [shown] on TV in most of the countries in the world, that’s quite a good way of raising awareness. So, this is a way of pressurizing politicians and pharmaceutical companies to make the drugs cheaply or freely available.[10]Media exposure involves securing television-advertising dollars for spots during concert broadcasts. But there are also innovative means of generating awareness and funds through new technologies in … Continue reading

The 46664 mega-concert is historically reminiscent of Live Aid because, as Geldof succinctly put it in his introductory speech from the stage, “if the condition is medical, the solution is political.” By “political,” Geldof refers to the fact that although antiretroviral drugs are now available, such that people can live long lives even while infected with the HIV virus, many people cannot afford the medicines, and governments are avoiding signing off on budget lines to support programs in order to provide them. Bono said that “the reason why Beyoncé is here is because she asked the right questions: ‘Why are 6500 people dying every day in Africa from AIDS?’ ”[11]Bono, “Interviews.” 46664 The Event, DVD, Disc 2. The social stigma from carrying the HIV virus, or being diagnosed with AIDS, prevented many governments from feeling they could place sufficient emphasis on allocating resources towards it.[12]“Stigma and Discrimination.” 2003. UNAIDS fact sheet <http://data.unaids.org/publications/Fact-Sheets03/fs_stigma_discrimination_en.pdf> (accessed July 15, 2010)

When the Thatcher government would not move on the issue of the Ethiopian famine in the mid 1980s, Geldof became enraged at seeing news documentaries of dying children appearing on his living room TV every evening and decided to fundraise by writing a song, “Do They Know it’s Christmas?” which became a number one Billboard hit in 1984 (and it has done so each time it has been rereleased or rerecorded with new artists).[13]The single was released first in November 1984, then rereleased in 1985. Band Aid recorded it with newer artists in 1989, and again in 2004. Each time it reached number one on the UK Christmas … Continue reading He also developed a charity tax shelter Band Aid to retain the proceeds, and a few months later created the Live Aid mega-concert telethon to raise more money. His populist intervention was effective amid the apparent inaction of African and Western governments and raised 150 million British pounds in donations, which were distributed in short and long term projects by a team of development experts.[14]See Bob Geldof and Paul Vallely. 1987. Is That it? Penguin, UK

In much the same way, Mandela saw the need for creating the 46664 Campaign to fight HIV/AIDS, a dedicated interventionist organization that would focus on fundraising and education through entertainment media—specifically needed where there is inaction of governments to make available sufficient funds for medicines, medical treatment centers, and education and prevention programs. Mandela’s embracing of the multi-artist collaborative philanthropic genre, the benefit mega-concert, was an important endorsement of this mass media vehicle, which illustrates the potential positive uses of broadcast media (television and the internet) and celebrity.[15]Jeffrey W. Cupchik. 2006. Rock-For-A-Cause—Music, Politics and Mass Movements: Theoretical Perspectives on the ‘Rock-Aid’ Phenomenon.” Comprehensive Examination, Department of Music, York … Continue reading

In response to Felicity Horne’s observation that the 46664 mega-concert cued inspirational tones by conflating the struggle against apartheid with the struggle against HIV/AIDS as a metaphorical “fight,” between the two there is a notable difference. Despite their similar use of the broadcast media, the NMF’s 46664 Campaign launch mega-concert was aimed at fighting the church policy in a different way than the combative approach the ANC took against the South African regime of apartheid. The church was against condom use,[16]In his analysis of the policy shifts in the Roman Catholic Church of South Africa between 2000 and 2005, Stephen M. Joshua found that while there were initially clinics set up for treatment of … Continue reading but multiple religions, faiths, and cultures within South Africa could be reached discursively, and metaphorically, through sung prayer. Appeals to spirituality (by Yusuf Islam, formerly Cat Stevens) and faith-based appeals (by Andrews Bonsu) through song—rather than hearing from the dominant power-laden structures of top-down church policy—offered fresh voices of non-violent opposition. Resistance was delivered in discursive and performative ways, utilizing the iconicity of celebrity and the emotive power of music with a sense of community.

In this context, it is not simply that Mandela was a source of inspiration for action, but the fact that Mandela himself had recognized the power of broadcast mass media. He chose the mass-mediated, mega-concert medium to deliver a swift and meaningful message of change needed in socio-sexual practices at the individual level. Reaching individuals, who could choose to act differently when faced with the opportunity to engage in sex with or without a condom, would be easier than trying to move the church policy to a different position.

Because Mandela had seen how the efforts of the global movement during the anti-apartheid struggle were boosted by the mega-concerts of 1988 and 1990, he understood firsthand how the mass media, with its cameras, would be magnetized by the multi-artist celebrity mega-concert, and would center attention on the HIV/AIDS issue. He knew that broadcasters likewise understood the opportunity of a mega-concert to use the discursive power of celebrity endorsements at a telethon, and they could sell their advertising time at a premium for several consecutive hours of live entertainment. The media broadcast conglomerates, multinational music companies, and the event’s product sponsors could all benefit, and all buy into the project and broader public message of youth education leading to greater global public health. Meantime, Mandela’s team and artist-organizers could creatively promulgate their essential message widely to anyone with access to media devices.

Mandela’s Mega-concert Legacy

Historically, Mandela himself had close connections with the transnationally broadcast, UK-led, Artists Against Apartheid (AAA) mega-concert events. Two mass-mediated cultural events were developed by London-based producer Tony Hollingsworth to raise international public consciousness about the apartheid regime in South Africa and thereby generate public pressure on outside governments to impose sanctions to end the inhumane regime. Due to Hollingsworth’s creative intervention, the multi-artist genre was powerfully employed during these two Mandela Tribute concerts (1988, 1990) and follow-up campaigns, and led the way for Mandela’s own 46664 Campaign. In 1988, Nelson Mandela was the focus of the concerts, becoming a cause célèbre. Campaigning for his release became an international movement. After his negotiated release from prison, in 1990, Mandela decided to make his first UK appearance by delivering a speech from the mega-concert stage at Wembley Stadium. He knew he could not have reached 600 million people otherwise. Mandela “clearly understood the power of what he was dealing with.”[1]Quoted in Reebee Garofalo, “Nelson Mandela, The Concerts: Mass Culture as Contested Terrain.” In Rockin’ the Boat: Mass Music and Mass Movements, ed. Reebee Garofalo. Boston: South End Press, … Continue reading On that occasion, Mandela said to the artists assembled:

Over the years in prison I have tried to follow the developments in progressive music. Your contributions have given us tremendous inspiration…Your message can reach quarters not necessarily interested in politics, so that the message can go further than we politicians can push it…We admire you. We respect you. And above all, we love you.[2]Garofalo remarked that with that comment Mandela himself “anointed the marriage of mass music and mass movements.” See Rockin’ the Boat, 65

The Cape Town 46664 Mega-concert

Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics along with Queen members Brian May and Roger Taylor oversaw the organizing of the inaugural 46664 mega-concert. Mandela had personally asked Stewart to help: “Nelson Mandela gave me his prison number and said it ‘could be used in some way, maybe as a song.’ And I approached the late Joe Strummer (of the Clash) to write words and Bono to sing, and I’d written this tune.”[1]Dave Stewart’s comment on the inception of the songs and mega-concert is given here in full: “Then I went in the studio with various people–Bono, Paul McCartney, and Anastacia–and started … Continue reading Once Queen and Paul McCartney came into the studio to start laying their own tracks, the project snowballed and became a bonafide effort to do a large-scale concert. Working together with the NMF, the idea was to use the concert as a launch for Mandela’s new initiative on the HIV/AIDS issue.[2]The Cape Town 46664 Campaign concert was followed on March 19, 2005, in George, South Africa where Annie Lennox was one of the main headliners and Will Smith acted as host. From April 29-May 1, … Continue reading Brian May and Roger Taylor went with known quantities from the UK for the look of the show, bringing in set designer Mark Fisher whose credits included the Rolling Stones and Queen. According to Fischer, “it was Brian and Roger who insisted on the huge Mandela statue, and as such, that single element determined much of the rest of the design.”[3]Moles, Steve. “Aids Day on Stage.” In Live Design. <http://livedesignonline.com/mag/aids_day_stage/> (accessed June 30, 2010). To give it a “slick look” for television, David Mallet was brought in from the UK as director of the broadcast.[4]David Mallet also directed the 46664 mega-concert from London’s Hyde Park, A Concert for Nelson Mandela (2008). In preconcert interviews at Cape Town, he explained that he needed 16-18 cameras … Continue reading Under Mallet’s direction, the show featured regular cutaways to Nelson Mandela and his wife to his left. Shots panning to Mandela’s right showed Oprah Winfrey, Mandela’s family, and Sir Richard Branson.[5]Richard Branson’s Virgin Airlines helped facilitate transportation as the official concert airline.

The continuous presence of Nelson Mandela characterized the whole event. Throughout the evening we saw Mandela in the audience watching the concert. And during the performances, a thirty-foot high statue of Mandela’s smiling face was the centerpiece of the stage’s set design. Moreover, the focal point of the concert was Mandela’s speech. During his public address, Mandela explained the use of his prison number “four, double six, six four,” indicating that it refers to the fact that he was the four hundred and sixty-sixth prisoner to be incarcerated at Robben Island in the year 1964.[6]On Robben Island, inmates were addressed by their number and not by their name, as part of the psychologically mechanized, institutional process of dehumanization. The number/name of the movement was borne from the struggle against apartheid—a reminder that no one should be reduced to a number from contracting HIV/AIDS.[7]During his speech from Cape Town, Mandela explained, “46664 was my prison number. For the eighteen years that I was imprisoned on Robben Island I was known as just a number. Millions of people … Continue reading

No other mega-concert in the previous thirteen years had focused on one person and his legacy as did the inaugural 46664 concert.[8]The 1988 and 1990 concerts did not center on Nelson Mandela’s legacy, as much as they highlighted him as the personification of the struggle during the anti-apartheid movement. Where possible, … Continue reading Mandela’s attendance, and climactic speech from the stage (or videotaped address),[9]During the Mandela Day 46664 mega-concert in New York City in 2009, Mandela was unable to attend, and instead sent a videotaped speech to address the audience at Radio City Music Hall. offered audiences a strong and reassuring example of ethical leadership. In the context of the 46664 Campaign, each concert served not only as a gathering force of inspired performances by African and Western artists, but also as a testament to Mandela and the possibility for courageous humane conduct. A member of the South African group, Bongo Maffin, put it this way: “Nelson Mandela made the people in South Africa free, now it’s time for us and Nelson to make sure that the world is AIDS free.”[10]Bongo Maffin, “The Interviews.” 46664 The Event, DVD, Disc 1. And, at the Hyde Park 90th Birthday Tribute 46664 concert, Mandela passed the torch on to youth to carry the movement forward, declaring, “Now it’s your turn.”

Artistic Design of the 46664 Campaign Launch Mega-concert

The Cape Town 46664 mega-concert was several months in the making: not the two months that Bob Geldof spent putting together Live Aid in 1985, nor the one-month that George Harrison took to organize the Concert for Bangladesh in 1971. There was sufficient time to organize the line-up and to create the dramaturgical narrative that would get the message across musically and discursively. Singing or chanting the number “46664” musically happens on five occasions during the concert, giving the event as a whole more musical continuity than perhaps any other mega-concert besides the Mandela Tribute concert during the anti-apartheid campaign.[1]Several artists who performed there had already written their own anti-apartheid songs.

Every mega-concert is a highly constructed event. The concert line-up serves both to endorse audience expectations and espouse cultural values in its dramaturgical narrative, wherein the opening and closing acts serve as powerful bookends for impactful messaging. Overall, the Cape Town concert exhibited a blend of themes within a distinct narrative. But it also featured a mix of musical performance genres, including: Jimmy Cliff’s reggae, The Corr’s Irish/Celtic sound, Eurythmics’ 80’s synthesized pop, Bongo Maffin’s kwaito (South African house and hip hop); and traditional African songs with Angelique Kidjo’s “Afrika” and Yvonne Chaka Chaka’s “Umquombothi” (meaning “African Beer”) among several other genres. The event’s setlist could be characterized as having ‘something for everyone’—both in the audience and watching at home—with frequent and deliberate shifts between “mini-sets” of Western (UK/USA) and African artists (see Table 1: Order of Events, Artists and Songs).

There were three performance segments of African artists, each flanked by performance segments of primarily European-based, UK/Irish, and USA artists. The first segment had individual performances by two Senegalese male singers, Baaba Maal and Youssou N’Dour. The second segment featured three female African performers—Angelique Kidjo from Benin West Africa, Yvonne Chaka Chaka from South Africa and Bongo Maffin—followed by white South African singer-songwriter Johnny Clegg. The third segment brought together Ladysmith Black Mambazo in collaboration on vocals with Irish band members of The Corrs.[2]The group has a history of collaboration with Western artists, especially the well-known album Graceland with Paul Simon. See Louise Mientjes. “Paul Simon’s Graceland, South Africa and the … Continue reading Finally, two white South African singer-songwriter pop artists, Danny K and then Watershed, gave performances. Perhaps most noticeable at the first 46664 event was a more complete representation of artists from South Africa and the African continent than in most other mega-concerts focused on Africa.

Musically, the 46664 Campaign themes and the “46664 Chant” were heard at key points in the concert. While this event was similar to previous mega-concerts, in terms of it being structured thematically around specific narratives, the periodic refrains to this participatory chant gave the concert program a greater sense of unity. Moreover, despite the diversity of performance genres and songs, the weaving of related themes was remarkably consistent throughout the concert, and included:

(1) Appeals to the “champion” in each person to exercise courage, symbolized by Mandela’s exemplary work. These include songs empowering the individual actor in different ways, including: Beyoncé’s intimate call to “my young ladies” to take care of their bodies; Brian May challenging male youth, “Are you a man?” in the song “Invincible Hope,” and later “We are the Champions” right before the finale; and Ms. Dynamite’s encouraging women to practice responsible, safe sex giving out condoms to use, not just as a stage prop.

(2) Frequent sentimental tributes to Mandela, often during improvised moments within a song. This is heard in Sharon Corrs’ intoning “Man-de-la” within Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s song, “Lelilungelo Elakho,” and in Baaba Maal’s shamanic calling out the name “Mandela” eight times to close out his set. Johnny Clegg also sang an anti-apartheid devotional song, “Asimbonanga,”[3]The lyrics are as follows: “Asimbonanga (we have not seen him) / Asimbonang’ umandela thina (we have not seen Mandela) / Laph’e khona (in the place where he is) / Laph’ehleli khona (in … Continue reading calling to Mandela behind the prison walls of Robben Island. Recollection of the anti-apartheid struggle was also personified in Peter Gabriel’s song “Biko,” a lament that recalls the life of activist Steven Biko.

(3) References to spirituality, the message of solidarity, and the need for family and community-wide spiritual support in Yusuf Islam (Cat Steven)’s introduction to his song “Wild World,” and Bono’s “American Prayer.”

(4) Appeals for funds embedded within songs written especially for the occasion and related with the telethon element of the event. Chiefly, May’s song “The Call” and Mandela’s fundraising bid for his new 46664 charity during his speech.

(5) Songs expressing care and concern, such as Baaba Maal’s song “Njilou” for AIDS orphans. “I want of think about one generation, who become orphans,” he says before performing; and, Queen and Roger Taylor’s “Say It’s Not True” with its somber calling out the “crime” of the unavailability of medicines for those infected with HIV.[4]Roger Taylor’s lyrics of the song “Say It’s Not True” point directly to the problem: “It’s hard not to cry / it’s hard to believe / so much heartache and pain / so much reason to … Continue reading

(6) Songs pledging love and affection for Africa, heard in all of the South African artists’ performances, including those of Yvonne Chaka Chaka, Angelique Kidjo, Youssou N’Dour, and Bongo Maffin.

(7) Appeals to romantic love and passion in Bono/U2’s “One” and “Unchained Melody.”

(8) Song reference to “Amandla,” the African concept of power (and empowerment) in Dave Stewart, Queen, and Anastacia’s collaboration on their new song, “Amandla.”

Each artist’s song performances were dramatically programmed to lead to the next part of the “story” within this overarching thematic schema. The next section of the paper describes the ways in which several of the above listed artists’ song contributions worked to achieve thematic continuity.

Weaving a Thematic Narrative

Beyoncé was a major headliner for the event, having just launched her solo career five months earlier. She opened the 46664 concert with her mega-hit, “Crazy in Love,” a highly choreographed number with six female dancers around her as she sang live. After her performance, she walked downstage and addressed the assembled audience in a soft voice: “I want to tell everyone out there, especially all of my young ladies…There’s nothing sexier than being confident and taking care of yourselves.” She then launched into a new melody based on the 46664 prison number. “Do you know the famous prison numbers of Mr. Nelson Mandela??” She sang, “four, six, six, six, four…” (c1, g1, f#1, g1, c1) with staccato eighth-notes on the first four pitches and a half-note on the fifth. She pranced playfully across the stage in a beguiling manner, in time with the catchy tune. Cutaway shots showed Oprah dancing and singing along in her chair, and then on her feet, participating with everyone in the sing-along “4-6-6-6-4” while sitting beside an apparently much charmed Nelson Mandela. These iconic celebrities and the crowd singing along to the numbered tune together were the focus of this moment. Beyoncé had temporarily transformed Mandela’s tragically serious number—meant on this occasion to symbolize the courageous transformation of overcoming isolation—into an opportunity to share in a playful and celebratory experience.[1]Even as she appeared in Cape Town, there was Grammy “buzz” centered on Beyoncé. She would go on to win five Grammy awards, tying Alicia Keys, Norah Jones and Lauryn Hill for the most Grammy … Continue reading

Video Example 1a

Video Example 1b

Another female artist’s powerful voice, Thandiswa Mazwai, from the group Bongo Maffin, closed out the concert. She sang solo cries of “Man-de-la” with legato notes on each of the syllables in rhythmic complement with the Soweto Gospel Choir’s chanting of Bono’s and Stewart’s lyric “four…six, six; six four” from their song “46664: Long Walk to Freedom” (discussed in detail below). As the artists exited the stage they did so in couples—many arm in arm, hugging each other and smiling—embodying the theme of solidarity.

For the first 46664 mega-concert, choices about who would give introductions to the next artist were simplified. Performers introduced each other rather than having a main host, or artist, come on stage to give a special introduction. Youssou N’Dour introduced Peter Gabriel after concluding his set, who introduced Yusuf Islam after finishing his. By contrast, the 46664 concerts of subsequent years had a dedicated host (for example, Will Smith and Jada Pinkett Smith co-hosted the Nelson Mandela 90th Birthday Tribute 46664 concert held at London’s Hyde Park in 2008).

At this event in Cape Town, having artists introduce each other kept the time down to a respectable length—a practical concern, since Mandela (at 85 years of age) had to be present for the entire length of the five-hour event in which his continuous presence was an expected highlight. Thematically, these transition moments telegraphed to the audience a sense of friendship and an air of collaboration that was in keeping with one of the concert messages: to maintain strength through solidarity in meeting this public health challenge.

As sociologist Christian Lahusen (1996) details in The Rhetoric of Moral Protest, the meaning and power of “performance” include the sonic aspects as well as those social and discursive acts that serve to frame a given performance.[2]Christian Lahusen, The Rhetoric of Moral Protest: Public Campaigns, Celebrity Endorsement and Political Mobilization. New York: De Gruyter Studies in Organisation, 1996, 259-260. He explains, following Erving Goffman’s notion of “dramaturgical narratives” (1974), how certain musical performances are extended to include cameos, endorsements, and other kinds of appearances by star celebrity actors and politicians who introduce songs and “throw”[3]A “throw” is Television shorthand for a style of introducing, often through a segue, the next artist, act or media (i.e., song or video). to the next act. One such cameo appearance at the 46664 concert was that of Cat Stevens, now Yusuf Islam, who had not performed publicly in years and became one of the headlining acts. Journalists also heralded the visit of “A-list” artists who had previously refused to perform in South Africa when invited to play a concert at the Sun City resort in Bophuthatswana.[4]Steven Van Zandt (“Little Steven”) wrote the song “Sun City” under Artists United Against Apartheid in 1985, after Live Aid to champion the artists who had refused to play at the concert.

One of the most important thematic refrains of the concert was spirituality. Cat Stevens began with an inspirational sermon before playing a collaborative version of one of his early hit songs:

I believe that where there is hope, there is a solution. I believe that what’s happening today with HIV/AIDS is something that can be solved through our shared humanity and our shared spirituality. We can do it. We need to strengthen the will to give to others, and we need to strengthen the natural love of family and of home. We have a song. This is a combination of something old and something new: “Wild World.”[5]Cat Stevens, “Wild World.” Island Records, 1970.

Musically reflective of the theme of shared spirituality, the song featured collaboration with the Soweto Gospel Choir and Peter Gabriel backed by Spike Edney’s house band. Islam (Stevens) weaved a heavily syncopated rhythm, which slowed down the melody and completely lost the scalar descending run of eighth notes before the line “It’s hard to get by, just upon a smile,” which was the original version’s signature hook. In an interesting way, the very absence of the hook made it a compelling, cross-cultural, hybridic example of what becomes possible through shared understandings.[6]Jimmy Cliff released a reggae cover version of “Wild World” on Island Records a few months after Cat Stevens’ original release (1970), offering a new rhythmic direction that reached number 8 in … Continue reading With his deeply deliberate gestures in conducting the tempo, the message seemed to be signifying the need to ‘slow down, and listen to each another.’ Musically, this bending and pulling at genres was not a large part of the first 46664 concert. Generally, artists performed their own songs or completely new songs. But in subsequent 46664 concerts, Spike Edney, musical director of the 46664 “house band,” revealed that collaborations between artists that resulted in doing songs in new ways were most interesting to him.[7]Before the Mandela Day mega-concert in New York City on July 18, 2009, Spike Edney revealed that his own musical tastes leaned in Cat Stevens’ innovative direction. Edney said, “I think you’re … Continue reading

The second song expressing spiritual identity, “American Prayer,” saw the return to the stage of Beyoncé with Bono, The Edge, and Dave Stewart.[8]The songwriters of “American Prayer” are credited as Bono, Dave Stewart, and Pharrell Williams, though Pharrell was not at the Cape Town event. Bono introduced this song, which he cowrote with Dave Stewart and Pharrell Williams, provocatively by recalling the theme of religion/spirituality in a more overtly politicized way:

It’s funny how “religious” people are sometimes the most judgmental. This is a song we wrote called, “American Prayer.” It could be Irish prayer or African prayer. It’s just a message to the churches that we really need you to open your door and give sanctuary and break the stigmatization that goes with being HIV positive. If God loves you…[Bono’s voice falling in exasperation], What’s the problem?

Asking for a rethinking, one of the rock world’s most outspoken activists supporting global popular movements of humanitarian concern, Bono questioned the then official policies of the church regarding HIV/AIDS. Within the context of mass-mediated artivism, such a mass appeal attempted to land a blow on the biopolitical body of a powerful global institution and could perhaps be heard in new ways.

A final aspect of the narrative presented in the concert were personal tributes to Mandela. These tributes often took the form of dedications and songs that recollected the artist’s involvement in the anti-apartheid struggle and became an important component of the event. This was evident in the way Peter Gabriel framed the dedication of his song “Biko” to both Mandela and Steven Biko:

This is a long time coming—both for getting to this issue and for me personally. After many years, having written this next song, waiting to play it in this country with my band, for you, for Madiba… with this choir here… It’s a very emotional moment. But most of all, this is for Steven Biko.

Gabriel had performed “Biko” as the finale to the 1988 Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute Concert in Wembley Stadium, while Mandela was still in prison.[9]Named, Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute, the mega-concert featured a line-up of 83 artists, who performed over the course of 12 hours, nearly double the number of artists and duration of the … Continue reading This nine-minute version, unlike the Tribute version, had less heightened angry energy and was more diffuse in its strong solemnity—which perhaps was only fitting.[10]With Peter Gabriel as the main performer, the televised shot that David Mallet used as a refrain featured, in one frame, an old photograph of Steven Biko’s profile looking in the stage right … Continue reading

New Songs Composed for the Inaugural 46664 Concert

Four new songs were composed for the concert event: Dave Stewart, Joe Strummer, and Bono’s song “46664 Long Walk to Freedom”; Stewart, Queen, and Anastacia’s “Amandla”; Queen and Paul Rogers’ “Say It’s Not So,” and “Invincible Hope.” These comprised a consistent, musically thematic thread, and offered a clear dramaturgical narrative.

Stewart, Strummer, and Bono’s “46664” song was significant because it encapsulated two themes of Mandela’s life: the time he spent incarcerated in a prison system in which he was to be treated as no more than a number, and his “long walk to freedom.”[1]The song lyric also refers to the book title, Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (1994). Instead of allowing himself and his fellow prisoners—as well as the prison guards on Robben Island—to fall prey to the systemic dehumanization, he energized a stand against the injustices of apartheid and sought equal rights for all persons living in South Africa. Symbolically, the two musical themes were interwoven, allowing for direct audience participation either by chanting the syncopated phrase “Four…six, six; six four!” or by singing with the Soweto Gospel Choir “It’s a long walk / Long walk to freedom.”[2]A musical analogy from a related genre will be helpful. Like the audience’s chant of “Thun…der” during the heavy metal rock band AC/DC’s live performances of “Thunderstruck,” here, the … Continue reading

“Four…six, six; Six four!” / “It’s a long walk”

“Four…six, six; Six four!” / “Long walk to freedom”

Within the bridge of Bono’s song, a third musical texture is added. Jamaican recording artist Abdel Wright is featured rapping the verse in double-time. During this audience participation section, the audience is lit up under floodlights and we see very clearly that, at least in the general admission section (the stadium floor), there are mostly white youth and middle-aged males, some females, and very few blacks. As Bono stands downstage, pumping his fist in the air in time with the audience, we see three large white male security guards resting their thick forearms and elbows in relaxed but intimidating certitude on the stage under him. There is, at once, a force of authority, protection, fandom, and love for Mandela, as the audience champions his new cause by chanting his new campaign name/former prisoner number. During the chanting, Mandela walks slowly onto the mainstage behind Bono wearing a black sweatshirt with the large numbers 46664 in white. He is helped across the stage to a podium by a white female personal assistant, who wears a 46664 T-shirt under her white cardigan shall. She holds her right arm in a bicep curl for Mandela to use as a second crutch (his cane is held strongly in his right hand). In hyped tones, Bono cheers, “Not just a president for South Africa. Not just a president for Africa. This is a president for anyone, anywhere, who knows freedom. Madiba, Nelson Mandela!” Bono goes up to the podium to hug him and Mandela responds warmly, saying “So nice to see you.” Dave Stewart approaches and kisses Mandela on the cheek. Like the televisual authority usually exhibited in the U.S. President’s State of the Union address to the U.S. Congress, during Mandela’s speech we see the former South African President flanked on his immediate right by Bono, The Edge, and Dave Stewart; and, on his left, by a bodyguard and a stagehand. Demonstrating respect, the 40,000 plus concert-goers cheer “Nel-son” repeatedly, in rhythmic unison. Smiling in return, and offering “thank you” several times, Mr. Mandela cannot begin his speech for two minutes.

When Mandela’s speech, centering on empowering women and girls, is concluded, amidst great applause, Brian May shakes Mandela’s hand along with fellow artists. Mandela is still only a few feet away when May shrugs apologetically (since exiting the stage is taking more time than expected) and strikes a bass-heavy power chord on his guitar. At this, Mandela gives him the “thumbs up” sign. This power chord “cue” leads into Queen’s performance of their second new song written for the occasion, “Invincible Hope.”

Set as a mini rock-opera, in Queen’s indelible symphonic-rock genre style, the purpose of this song segment is to lead out from Mandela’s rousing speech and channel the inspiration into action. Highly programmatic, it begins with Mandela’s recorded voice over the speakers asserting, “Dignity, the hallmark of our action. Shaking hands with history. The struggle is my life. I will continue fighting for freedom until the end of my days.” Then, singing masterfully in Queen’s progressive rock style, the Soweto Gospel Choir enters with clipped, clearly enunciated, eighth-note marcato accented blasts of syllables: “Have in-vin-ci-ble faith! Have in-vin-ci-ble hope, in the in-vin-ci-ble dig-ni-ty of man!” …Silence… After repeating this three times, May moves downstage to the microphone, looks directly into the camera, and speaks in a serious, compassionate tone: “Make the Call.” He mimes entering the five digits into a telephone’s push-button keypad, while the pitches of the keypad sound over the speakers, beeping in-sync with his gesture, “4-6-6-6-4.”

The rock opera continues with lyrics referencing Mandela’s achievements, punctuated finally with the challenge: “Are you a man, or just a number?” The Soweto Gospel Choir chants, “four…six, six; six four” in precisely the same rhythm that Bono had the audience chant before Mandela’s speech. As they do so, Brian May stands firmly, with legs wide apart and one fist in the air, in fantasy rock-opera style, calling upon young males seeking a protagonist-come-superhero to become the heroes themselves. May urges them to engage in action:

Now! Help. We need you. Your world needs you. Needs you to stand up. Needs you to take action and say, “No!” This will not happen! It shall not be one law for the black or the white. It shall not be one law for the man, one law for the woman…for the heterosexuals…for the homosexuals, for the rich countries…for the poor countries.

Grinding to a swift halt, May allows another moment of dramatic silence before he challenges again: “Are you a man? Make the call…Wherever you are! Please. Make the call.”

The telethon was an important aspect of the mega-event. Queen’s Brian May and the other main artist-organizers did most of the persuading of viewers at home to donate. Additionally, during his speech, Mandela requested viewers to “go to the website, and you can call and pledge your support to a local [telephone] number.”

Christian Lahusen contends that “simplicity” is prerequisite to success in a political campaign. The intention of campaigners is always “to guarantee the clarity of their statements and messages. This translates into the simplicity and parsimoniousness of sign production. Simplicity means the reduction of the political issue’s complexity to a manageable statement.”[3]Christian Lahusen, The Rhetoric of Moral Protest, 1996: 259-260.

Thus, to make it easy to donate funds during a mega-concert telethon, where personal energy and commitment is required, innovative technologies can provide a new vessel for “passing around a hat.” By texting the numbers 4-6-6-6-4 on your mobile phone, local and global audience members could automatically donate $10.00 USD to the 46664 Campaign. If you could not attend the 2003 event in Cape Town, afterward you could buy the DVD or three separately released 46664 CD albums. But Queen’s integrating the fundraising “ask” within a rock opera was a neat trick.

Two more newly composed songs with layered messages, written specifically for the Cape Town event, return to the theme of spiritual strength in overtly religious ways. Andrews Bonsu, a 13-year old male, in rhythmic elocution with the groove of the song “Amandla,” delivered a sermon, an evangelical-styled Christian prayer, asking “Father Jesus Christ” to help find a cure for HIV/AIDS. Behind him, Beyoncé, Dave Stewart, Bono, and Anastacia held their heads in repose respectfully before lifting to cheer with the audience at the conclusion of his impassioned plea to relieve the suffering those with the disease. The song “Amandla” references the local Xhosa and Zulu word meaning “power,” referring to empowerment, and was written in collaboration with Dave Stewart, Bono, Anastacia, and Queen. Largely a soaring melodic flight near the top of her powerful voice, Anastacia sang with Beyoncé, Bono, and Youssou N’Dour.

Religious tones were noticeably invoked in Ms. Dynamite’s rap/dub poetry number in which she likened the HIV virus to the devil, gently demonizing those innocents who would allow the silent killer to enter their bodies disguised under passion. Wearing a white T-shirt with four words written on cardboard cutout pieces taped on it that read “respect yourself, protect yourself” (as if to ward off the devil), she gave the most direct message of the evening. She advised “all my young sexy ladies out there” to disallow access to male sexual partners who would not wear a condom and then quickly distributed condoms by hand to the women in the audience who were closest to the stage. Her main point was stated in the title of her song, “Don’t Throw Your Life Away.” The theme of practicing safe sex—warning of the threats of unchecked sexual practices when under the spell of impassioned love—cleansed the musical palette (and gave the house band a short break) before the extended finale.

Bono and The Edge began the finale with an austere rendition of their hit song, “One,”[4]“One” was the fourth single U2 released from their 1991 album, Achtung Baby, on Island Records, which reached number one in Canada and Ireland, number 7 in the UK and number 10 in the USA. and Bono respectfully lit a single, white, wax candle “for a friend in Cape Town who died yesterday.” This mood was drawn into a deeper sense of spiritual intimacy by following up with the familiar romantic love song, “Unchained Melody,” which Bono began, and the audience sang mostly on their own as Bono held the microphone out towards them. The Righteous Brothers’ 1965 hit song had been featured in a scene in Ghost, a Hollywood film, with imagery of impassioned love between a couple, one living (played by Demi Moore) and her recently deceased partner (played by Patrick Swayze).[5]The song “Unchained Melody” was first recorded in 1955. Alex North wrote the music, and Hy Zaret wrote the lyrics. Song choices that referenced losing a loved one were registered as another thematic refrain articulated by the artists.

Religious or Spiritual: A Public/Private Distinction

With attention to the distinction between “religion” and “spirituality” noted above, and a wish to not commit any missteps by conflating the two, it will be helpful here to define terms. In practice, the terms “spiritual” and “spirituality” are employed as part of a health-related construct in health research, a domain in which social, emotional, and cognitive meanings are often addressed in end-of-life care, reproductive care, and birthing practices, among other healthcare settings, in order to better understand the social determinants of health and well-being. This contrasts with the terms “religion” and “religious,” which are often oriented to the social sciences or humanities in their usage. Some religious studies scholars bristle at the mention of “spirituality” because of its vagueness unless locally grounded meanings are explained. In practice, however, health researchers will use the terms “spiritual” and “spirituality” in their ethnographic interviews. Because of the less focused meaning of “spirituality,” eliciting responses regarding preferences for one’s spiritual care, for example, can result in multivalent responses, and this is considered to be an appropriate approach within the model of patient-centered care. Whereas discussing one’s religion, house of worship, denomination, or level of observance can sometimes bring up uncomfortable connotations and memories for people who have experienced trauma in institutional religious settings.

In the area of ethnomusicological scholarship that focuses on community settings in which healing rituals are performed for and with individuals or congregations, researchers often work to understand the role of context, faith, and belief.[1]See the edited volume by Carol Laderman and Marina Roseman, eds., The Performance of Healing. New York: Routledge, 1996. See also Lawrence E. Sullivan, ed. Enchanting Powers: Music in the … Continue reading Explorations by ethnomusicologists into this domain, utilizing ethnography as a key methodology in these performance settings, include Gregory Barz’ work on the role of music in communities struggling with HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Barz found that many individuals in faith-based rural communities publicly draw a strong distinction in reference to these domains, whereas privately there is a blurring across such lines. He writes, “[C]ommunities often publicly denounce the efforts of traditional healers regarding HIV/AIDS,” while “privately, people often avail themselves of a variety of healing systems, especially when HIV is involved.”[2]See Gregory Barz. Singing for Life: HIV/AIDS and Music in Uganda. New York: Routledge, 2006.

In the context of the Cape Town mega-concert, educative action was paramount and included narrative techniques and performance approaches to inspire and cue responsible social and sexual health practices. Some artists’ calls to educative action, such as Andrews Bonsu’s lyrical prayer, drew upon themes of faith-based religion, showing how religious belief may be invoked in healing practices, especially within the embodied realities of a religious community where many have experienced profound losses due to HIV/AIDS. Other artists referenced not religion per se, but spirituality, which made sense for reaching a youth population affected by interracial tensions, and seeking social transformation without the baggage of authoritarian dogma.

Amid the atmosphere of camaraderie fostered by respect and admiration for Mandela, performers cycled through a succession of 46 acts of featured artists in the concert line-up. They were organized in such a way that they symbolized, to an extent, an exemplary exhibition of gender and race parity, representation from different generations, contrasting regions and communities, and differing beliefs and practices—all affected by the great equalizing factor of collective mortality due to HIV/AIDS. That is to say, in spite of culture and language differences, and musical preferences, the humanitarian factor of mortality leveled the playing field in Green Point Stadium.

Perhaps the most significant conceptual paradigm at work, from a postcolonial perspective, was the symbolically draped pan-African flag of Amandla (power) that is understood to not be localized in any one country or region, but meaningful to the continent as a whole. Thus, in terms of the religion/spirituality divide, the concert’s narrative was not counter-religion, but appropriately welcoming of religious or spiritual sentiment while being opposed to valorizing church policy on condom use. Reference to Amandla does not mean the concert was dressed in a rhetoric of “new age” faux spirituality; rather, it was appealing to each individual for the sake of health and well-being, in which Amandla was evidently ready to be activated personally and in community.

The concert offered a mix of narratives for different persons and persuasions. The theme of spirituality dovetailed with the broader narrative of empowerment, and yet against the anti-condom use policy of the church. The concert narrative was careful to be pro-religion and pro-spirituality while being critical of church policy. Thus, the event was not anti-religion. For example, in the narrative presented, spirituality was evident, whether in traditional religious themes or in contemporary interpretations. Musical references to Amandla and ubuntu as emerging from African sensibility and spirituality were part of a rhetorical strategy of utilizing indigenous concepts “writ large” as authoritative. The underlying idea was striving for authentic engagement in the community, and actions and aesthetics embodying holism.

The inaugural mega-concert was an effort to reach everyone who was listening by means of an overarching, all-encompassing, narrative. Whichever minor storylines worked alongside were permissible within the major dramaturgical arc of recalling the relatively recent historical example of Mandela’s moral courage in facing down policies that proved deleterious to a society seeking emergence into a late 20th-century global economy. He had addressed inequities before in the interest of, and on behalf of, South Africans in symbolic and structural ways. Now, the broader appeal to each individual’s moral courage was symbolized in Mandela’s prison number, which called attention to the responsibility of each person to acknowledge the power of decision-making, and the ability to effect change with the relative freedom s/he has. The pan-African and local symbols could be cultural supports for individuals acting responsibly, amid a global public health crisis exacerbated by social, political, and religious factors, which needed to be addressed more effectively in South Africa.

What made sense of the complex weave of different types of “calls to action” that concerned social responsibility was the hard and fast reality that on the ground in several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, and certainly in South Africa in particular, a health crisis had been growing for several years. Mandela’s 46664 Campaign launch was utilitarian in that multiple strategies were deployed to corral the sentiments and emotions of the various youth who needed to take a greater level of responsibility for themselves as well as for public health—regardless of their religious and/or spiritual identities. Politicians, schools, and community service organizations were at work developing and implementing sexual education programs that could explain the need for change in the social and sexual practices among South Africans, but the church’s powerful rhetoric and stance was leaning the other way, causing a strain on the ability of local organizations to stand and connect with individuals on condom use education.[3]See Endnote 22. See also Joshua’s article drawn from his Ph.D. dissertation, published by the journal of the Historical Association of South Africa, entitled, “ ‘Tell me where I can find the … Continue reading

Evaluating and Understanding Mega-concert Outcomes

The macro-level interests of campaign organizers appear to place emphasis on results-oriented evaluations of event outcomes. In terms of consciousness-raising, and changed practices, there is progress.[1]“Progress in Countries.” 2006. UN AIDS Fact Sheet. <http://img.thebody.com/legacyAssets/06/58/progress.pdf> (accessed July 15, 2010). The UNAIDS report, conducted by the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS working in tandem with the World Health Organization, noted changing trends in socio-sexual practices. In South Africa, the proportion of adults reporting condom use during their first sexual encounter rose from 31.3% in 2002 to 64.8% in 2008.[2]“UN AIDS Fact Sheet.” 2009. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. World Health Organization. <http://data.unaids.org/pub/FactSheet/2009/20091124_FS_SSA_en.pdf> (accessed June 20, 2018). Condom use was a major theme of the 2003 concert. More broadly, Sub-Saharan Africa made progress in expanding access to services aimed at preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. With respect to cases of increased access to antiretroviral therapy, in 2008, 45% of HIV-positive pregnant women received antiretroviral drugs, compared with 9% in 2004.[3]“UN AIDS Fact Sheet.” 2009. Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and World Health Organization. <http://data.unaids.org/pub/FactSheet/2009/20091124_FS_SSA_en.pdf> (accessed June 20, … Continue reading Despite these significantly positive trends, since the causes which lead to social change are interdependent, and often cultural, it remains unknown the extent to which these results could be attributable to Mandela’s 46664 Campaign.[4]While cause-effect relationships are difficult to attribute with certainty, Barz maintains that journalists, documentarians and a host of other workers “share a common interest in understanding the … Continue reading

When making assessments of the impact of this relatively new kind of cultural event, it is vital to attend to the fact that the goals of each mega-concert and “political” song vary (Ullestad 1987; 1992). The goals of Live Aid (“Media Aid” or “charity-rock”) differ from the more politically adroit Mandela Tribute concerts or the 46664 Campaign’s goals of “education,” “raising awareness,” and “fundraising.”

One strategy of evaluation, when measuring the success of mega-concerts, involves following the goals set by Tony Hollingsworth for the two Mandelaanti-apartheid mega-concert events as a guide.[5]To look into this in greater depth, more analysis of the influence of ‘rock-aid’ events is required. Further research ought to include questions about: (a) the change to artists’ careers – in … Continue reading Garofalo (1992b: 26) finds these provide “useful categories for assessing the impact of mega-events.”[6]Garofalo may be limited by utilizing this set of criteria for evaluating all megaevents rather than espousing different evaluative strategies for each different type of ‘rock-aid’ event. While … Continue reading Hollingsworth’s four functions of the Mandela Tribute concerts, as he saw it, were:

Fundraising; consciousness raising (“to raise the profile of Nelson Mandela’s name as the symbol of fighting against apartheid”); artist activism (“to demonstrate to the world and to South Africa the enormous popular and artistic support for all those who fight against apartheid”); and agitation (“to make the show act as a flagship…whereby the local anti-apartheid movements could pick up from the enormous coverage that we had and run a far more detailed political argument than you could have on a stage.”)[7]Tony Hollingsworth. “Panel on Mass Concerts / Mass Consciousness: The Politics of Mega-Events.” New Music Seminar. New York. July 17, 1989, in Garofalo 1992: 26.

Let us initially consider the first of these five categories with respect to the 46664 mega-concert. Fundraising is a significant marker of a mega-concert event’s raison d’être. Bob Geldof’s speech that opened the 46664 inaugural mega-concert may have misled people to believe raising money was not one of the goals of the concert or the foundation. He announced, probably mistakenly:

My job is to welcome everyone here and everyone at home watching and to point out that it doesn’t matter how much or how little this concert raises in money because AIDS has moved beyond that now. It’s simply another medical condition.[8]Geldof goes on to say, “But if the condition is medical, the solution is political” which is quoted earlier in the paper. As a rhetorical strategy, Geldof’s de-emphasizing the financial aspect … Continue reading

Robbie Williams, concert producer for the 46664 Cape Town event was under the same impression as Geldof: “It was never the intention for the actual show to make money…Its whole purpose was to launch ‘46664’ worldwide.”[9]“Behind the Concert.” 46664 The Event, DVD, Disc 1. But six years later, Mandela released a videotaped address to the press about the upcoming 46664 “birthday” concert, correcting the viewpoint of Geldof and Williams. Gazing intensely into the camera, wearing a tiger patterned white and black silk shirt, he leaned forward and stated in cautious tones that he has agreed to attend the 90th birthday party concert held for him in London “provided that the concert raises money towards our charity.”[10]Nelson Mandela. 2008. “46664 Concert Honouring Mandela at 90 – London, 27 June 2008.” See Mandela’s address <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCXsaJI-bro> (accessed June 10, 2017), … Continue reading

Mandela’s team of artists and organizers considers the multi-artist 46664concert to be an integral part of an ongoing broader strategic campaign. To sustain this campaign, 46664organizers hold annual concerts rather than a one-off event. In this light, I suggest that a fifth categorical function, that of a ‘commitment to continuity,’ may be added to Hollingsworth’s four functions (above).[11]The 46664 Campaign mega-concerts have been held in Cape Town, South Africa (2003), George, South Africa (2005). Other 2005 concerts in Madrid took place over three nights and were divided into … Continue reading

Mega-concert Typology and New Evaluative Schema

Neal Ullestad, popular music historian, notes that it is important to differentiate between two basic types of mega-concerts: those that function primarily as “charity-rock” benefits, and those that agitate for political change. Ullestad pursues an interesting tactic by drawing a contrast between what he calls “Media Aid” (his neologism) and other “rock aid” music projects more “political” in nature. The 46664 mega-concert is a unique combination of both. I suggest that the typology noted above—of “charity-rock” fundraisers and the politically directed movements—could be revised to reflect Mandela’s 46664 Campaign launch concert at Cape Town, which combines both types of mega-events in the service of five strategies:

(1) Increasing social awareness of the HIV/AIDS issue locally and globally through symbolic leadership: Nelson Mandela’s speech, Oprah’s presence and participation, Beyoncé’s advice to the targeted demographic of young women, and other superstars’ messages in their song choices, introductions to songs; and inventiveness in creating new songs around “46664”

(2) Developing an artist community-led response: A-list artists modeling cooperation by working together on the event and collaborating artistically, e.g., Bono leading the audience in a 46664 “chant”

(3) Fundraising from the stage, exemplified through Brian May’s “Invincible Hope” song’s chorus to “Make the Call,” emphasizing the telethon aspect of the event

(4) Educative effect of women “performing” preventive strategies as model behavior, such as UK-rap star, Ms. Dynamite, whose song and performance art encouraged condom use; and related post-concert follow-up events and education programs to capitalize on the energy and interest in social change, and

(5) Commitment to continuity: holding annual mega-concerts, rather than a one-off event, builds in a long-term fundraising strategy and an ongoing artist-led response to the public health crisis. Unlike other mega-concerts that have provided funds for emergency relief and recovery, the HIV/AIDS crisis required an enduring movement, such as that advanced by the 46664 Campaign.

Mega-concerts, Celebrity and Mass Messaging

The role of music and celebrity to influence and inspire sociopolitical change is well known. What aspects of the 46664 Cape Town mega-concert would be deemed inspirational? Consider U2’s participatory “46664 Chant,” which evokes the sustained, and collective, effort required for this campaign. The song’s simultaneously accompanying melody “It’s a long… walk… / Long walk to free…dom” symbolically suggests that the challenge of addressing and ending the HIV/AIDS crisis will require global cooperation and a high degree of patience. The musical structure of this song’s chant, as with the choreographed song line-up of this mega-concert, gives the sense of a constancy of purpose and unified commitment through a diversity of respected voices. Whether joined in joyful tribute, in spiritual camaraderie, or in a courageous stand, a thematic fabric is woven throughout the 46664 inaugural concert’s dramaturgical narrative. The globally televised/broadcast mega-concert telethon for the campaign launch symbolically represents a cooperative transnational, mass-mediated struggle.

Hardly contradictory, a song can have an audience of one, or two billion. In the YouTube generation where “going viral” can be socio-politically life-changing, artists’ outreach through online media may carry a message effectively. Each year, artist-organizers have modified the strategy of the mega-concert telethon in accordance with the 46664 Campaign by adapting to newly available technology, and by attending to locally relevant themes with site-specific sensitivity to the cultural geography, broadcaster’s interests, youth culture’s expectations, and local artists’ wishes to participate.

As an example, the campaign slogan, “Give a minute of your life to AIDS,” placed the emphasis on inspiring personal agency individual action to promote the 2009 New York City-based 46664 mega-concert. A large-scaled filmic and visual display at Grand Central Station[1]Grand Central Terminal (aka. Grand Central Station) is a major commuter rail terminal in midtown Manhattan. It is a 13-minute walk from Grand Central to Radio City Music Hall. highlighted the global launch of July 18 as Mandela Day, and attracted visitors from all over the world to come and “spend 67 minutes in the service of others in honor of the 67 years Nelson Mandela had spent serving humanity.” This was the first 46664 mega-concert staged in the USA, and was held a few blocks away from Grand Central at Radio City Music Hall. Billed as Mandela Day: A 46664 Celebration, the mega-concert featured many African America artists, whose songs became thematically appropriated into the overarching theme of celebration despite their original meanings. Such thematic transformations included the way Gloria Gaynor’s classic, “I Will Survive,” and Aretha Franklin’s “Make Them Hear You” could be heard in light of the struggles Mandela had championed. Stevie Wonder led the finale song, “Happy Birthday,” to close the Mandela Day mega-concert.[2]See Stevie Wonder leading the song,“Happy Birthday,” which he composed to honor Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. during the campaign to establish Reverend King’s birthday as a national holiday in … Continue reading

Although the slogan, “awareness and education through entertainment,” may sound like a facile motto for the opening of the 46664 Campaign, given that education is one of the most powerful weapons to combat HIV/AIDS, and recognizing the global flow and reach of the popular music and web/film industries, such imaginative and coherent campaign strategies could be used effectively to magnify the potential for social change and possibly improve health outcomes.

Youth leadership and participation is one key to social change. As long as the suggested activity is considered to be “cool,” evolving social practices will shift accordingly. Capitalizing on the powerful influence of celebrity endorsements, many kinds of 46664 “products” and “experiences” could be “sold” globally—including the ideas carried by campaign messages. Consider the idea/ideal that health benefits will accrue following consciousness-raising, such as caring for one’s own body and those of others with equal amounts of compassionate awareness.

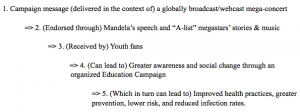

Figure 1. Artivism Process to Address Health Crises with a Campaign Mega-concert

The above equation, while marked by a rather presumptive linear and theoretically idealistic chain of events, illustrates one way of understanding the campaign strategy underlying the 46664 mega-concerts. The concert’s message of promoting health and well-being through illness prevention was directed primarily at women and youth. The goal was to inspire young women to become better educated about, and act upon, the importance of changing normative socio-sexual practices. The themes of self-care, and acting with a sense of personal responsibility and individual courage, despite social pressure, were conveyed in Mandela’s prioritization of young women’s health. Mandela’s courage in confronting sociocultural and political obstacles allowed him to offer his country’s youth a message from the stage, as a chief, father, and statesman of the new “rainbow nation” in a free South Africa—imploring everyone to act responsibly in socio-sexual practices, a relatively closeted subject.

Mandela's Decision to Use a Mega-concert Event

Mandela’s decision to utilize the mass-mediated mega-concert genre to educate, raise awareness, and fundraise for the HIV/AIDS 46664 Campaign, made sense to the NMF and the artist participants because they had seen this mode of communication work when energizing global commitment to ending apartheid. Mega-concerts proved to be effective maneuvers in 1988 and 1990. The 1988 concert was framed as a birthday “tribute” to Mandela (and actually titled, Nelson Mandela 70th Birthday Tribute), yet its power lay in the irony that Mandela could not be present at his own birthday party while he was still in prison. This was Tony Hollingsworth’s idea, a rhetorical sleight of hand that piqued everyone’s curiosity. Many people learned about who Nelson Mandela was for the first time because of the huge media publicity campaign around the concert. The 1990 concert was Mandela’s first public appearance in the UK after he was released from prison.

The two London concerts functioned together partly as bookends, and a narrative was created whereby the collective global action during the interim two years saw the result of public agitation whereby broadcast media displaying civic participation led to global public opinion change. Local AAM (anti-apartheid movement) chapters used smaller scale AAA events to pressure their own governments to, in turn, levy pressure in the form of sanctions against the apartheid regime in South Africa. Due to their effectiveness, and Nelson Mandela’s commitment to a national and global effort to eradicate HIV/AIDS (if only for the sheer numbers it was decimating), once his 46664 Foundation was established, his medium of choice for publicizing education and engineering a change was mass media and a mega-concert where multiple genres could be heard by multiple audiences simultaneously.[1]Nelson Mandela wanted HIV/AIDS to become normalized as had other diseases like TB or cancer, without the associated stigma and baggage, in order to enable rapid diagnosis and treatment. He disclosed … Continue reading